How managed services are building systems for corporate legal work

Illustration by Brenan Sharp and Stephen Ravenscraft

In 2011, the ABA Journal initiated a series of reports on the shifting paradigm of law practice. This series looks at how the legal business is responding—and the legal profession often not responding—to pressures never before placed on lawyers and law firms: a maturing market, disruptive technology, economic recession and the rise of legal services competition.

This article, written by law professor William D. Henderson, who helped initiate the Paradigm Shift series, looks at managed services—a new category of legal firms that build systems to handle high-volume, repetitive work—and how they’re making millions of dollars from the effort.

My research on the legal profession has enabled me to study rainmakers up close. Jane Allen, founder of Counsel on Call, based in Nashville, Tennessee, certainly fits one of the profiles.

Allen is affable and easy to talk to, getting high marks as a conversationalist because she asks good questions and seldom has to talk about herself. Her eyes and body language convey that she is listening and interested. As the dialogue continues, you share your problems and concerns. Allen then provides some keen insights that make them seem smaller and more tractable. Thus, in the most natural and sincere way, Allen becomes indispensable to your decision-making process.

This is how she goes through life. And, as it turns out, some of the people she talks to have legal problems. In the late 1990s, Allen had her own problems to solve. She had the resumé of a successful corporate lawyer—an honors graduate of the University of Kentucky College of Law, executive editor of the school’s Kentucky Law Journal, clerkship with a federal judge. But the arrival of her third child made the demands of her full-time law firm practice with Trauger & Tuke in Nashville incompatible with her personal goals. She negotiated a new work track in which she obtained a more flexible schedule in exchange for a reduced hourly rate for clients.

This new work arrangement had a big appeal to other female attorneys. Being a natural problem-solver, Allen decided to start a business called Counsel on Call in 2000 that made these capable lawyers available to other law firms to help with peaks in workflow or fill a temporary position.

A few months after opening, Allen got a phone call from Cathy Sowers, then the head of litigation for health care giant HCA, one of the largest employers in Nashville.

“Jane, you’ve missed your market,” Sowers said. “More than law firms, legal departments need high-quality specialized lawyers to cover things like family leave or staff a temporary surge in work.”

Almost instantly, Allen’s small-firm practice was transformed into a business that managed a large stable of high-quality, on-demand lawyers.

Jane Allen is the founder of Counsel on Call. Photo by David Mudd Photography.

By the mid-2000s, Allen’s high-powered clients were complaining about the inefficiencies of law firms and the lack of credible alternatives. She offered to collaborate with them to create teams of specialized lawyers. By 2007, the volume of work was sufficiently large that Counsel on Call opened its first managed services center in Nashville.

In 2007, Allen had never heard the term managed services. The layering on of vocabulary from other industries would happen a few years later. But with growing demand, additional centers would open in Atlanta and Dallas.

Counsel on Call is a growing $50-million-per-year business that employs more than 1,000 lawyers (as W-2 employees, not contract workers), does work for one-third of the Fortune 100, and operates in the United States and Europe.

A NEW LEGAL BUSINESS

Counsel on Call is one example of legal managed services, but there are many others, including Axiom, Elevate, Pangea3 and UnitedLex. Legal managed services providers design, build and staff process-driven systems that efficiently complete legal work. The work’s content often is sophisticated and important to the client’s long-term commercial interests. Yet the volume is too large to be performed cost-effectively by law firm associates and too narrow and repetitive to warrant hiring more in-house lawyers.

E-discovery is a prominent example of the managed services business model. But the number of additional use cases is growing and now includes corporate due diligence; internal investigations; contract management; patent valuation and portfolio analysis; and compliance programs that surround employment law, corporate governance, cybersecurity and data privacy.

Although the initial driver for using a managed services provider often is cost, additional advantages include quality, timeliness and transparency. In-house lawyers come to depend upon the metrics that enable them to monitor, measure and evaluate the large volume of legal work under their supervision. These metrics also are used internally to demonstrate to chief financial officers and CEOs that legal departments are making wise sourcing decisions.

William D. Henderson

If someone logs in to the Dun & Bradstreet Hoovers database and searches for Counsel on Call or other legal managed services, they’ll see that these companies are listed under the North American Industry Classification System as 541110 Offices of Lawyers.

That’s the same designation given to Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, Jones Day and your local general practice solo. Yet in contrast to a law firm, these companies are substantially or wholly owned by nonlawyer investors. Axiom and UnitedLex are backed by venture capital companies. Counsel on Call has been majority-owned by Gridiron Capital in New Canaan, Connecticut, since 2014.

(Counsel on Call was formed as a C corporation—it’s taxed separately from its owners—with Allen’s husband, Greg, who is a fellow shareholder and a businessman.)

If you are a lawyer and wondering how these finance methods are possible under ethics rules that bar nonlawyer investment, you should direct your inquiries to Lucian T. Pera, a legal ethics specialist at Adams & Reese and Allen’s longtime lawyer. Pera also is chair of the coordinating council of the ABA Center for Professional Responsibility and the incoming president of the Tennessee Bar Association.

In a nutshell, Counsel on Call and other managed services providers are attorney-to-attorney businesses. They contract with in-house legal departments to supply lawyers with specialized domain expertise, combined with access to outstanding technology, process and business know-how. Counsel on Call attorneys work under the direction of in-house or outside legal counsels.

According to the 2012 economic census survey, released by the U.S. Census Bureau, more than three-quarters of all legal services are sold to organizations (mostly corporations) rather than individuals. Obviously, larger organizations tend to have general counsels. The addressable market for legal managed services providers is the same market pursued by the Am Law 200.

A SEGMENTED MARKET

The first time I heard the term managed services was in April 2013. Law professor Dan Katz of Chicago-Kent College of Law and I were interviewing Mark Harris, then the CEO of Axiom, as part of a documentary film project on new legal services providers. Arguably, Axiom had the most distinctive brand in this space, as its rise had been chronicled extensively in the legal press.

Sitting in a conference room in Axiom’s San Francisco office, my first question was: “Have you won yet?” Harris replied, “I feel like we have just gotten to the starting line.”

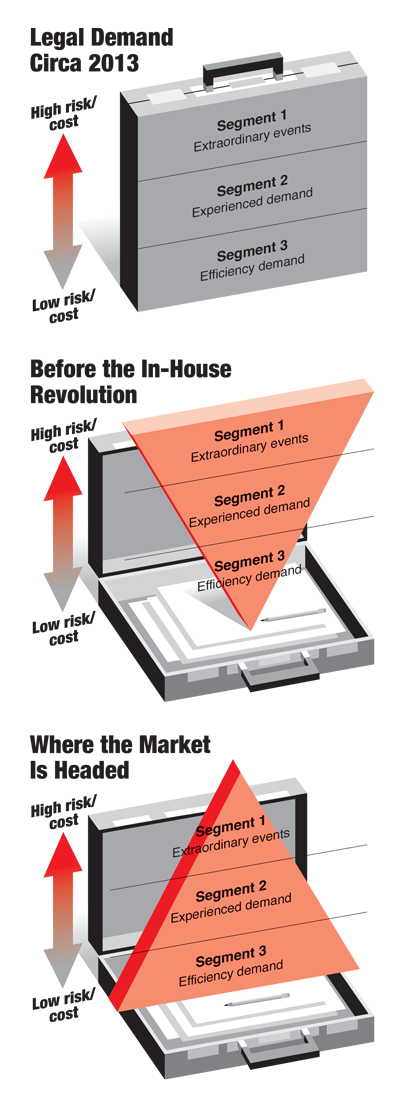

Illustrations by Sam Ward

Harris then explained how the company was at about $50 million per year in revenue in 2008 when the financial crisis hit. Before that time, the client mindset was one of interest, but not urgency, toward companies such as Axiom. But after 2008, there was “real demand for a different way of operating.”

Although demand for legal services finally rebounded, complexity (what Harris called the “third dimension”) continued to increase because of the blurring of geographic boundaries and the proliferation of new and more novel regulations. This created cost pressure that could only be solved by quantum leaps in lawyer productivity.

As a result of the change in client mindset, Harris explained, Axiom was able to achieve a size, scale and geographic footprint that made the company credible to the world’s biggest and most significant corporate clients.

“Now we are here. We are in the game—12 years to get into the game, to get our ticket punched,” said Harris, who co-founded Axiom in 2000. “We are finally in a position where we can build something transformative.” By 2013, annual revenue exceeded $150 million.

That transformation will happen, according to Harris, because general counsels are being forced to fundamentally rethink the perceived zero-sum trade-off between risk and cost.

“Ultimately, the part of our business that will be most instrumental [in making this shift] will be what we call managed services,” Harris said.

Struggling to explain this concept, Harris dragged a whiteboard into the room and began to draw. The first diagram (labeled “Legal Demand Circa 2013,” facing page) was rectangular. This reflected the segmentation of the corporate legal services market into three parts: extraordinary events (Segment 1), experienced demand (Segment 2) and efficiency demand (Segment 3). As the type of work moves from bottom (efficiency) to top (extraordinary), Harris said, a perception among lawyers and clients is that cost and risk invariably have to move in unison.

“If you go back in history, there was one transformational moment, and that was when the modern law department was created—with [general counsel] Ben Heineman at General Electric,” Harris said.

Drawing an inverted triangle with the legal departments at the bottom (labeled “Before the In-House Revolution,” above), Harris claimed this change was primarily an exercise in segmentation, as GE and other legal departments realized “there are serious savings available with John as an employee of GE rather than John as an employee of Cravath.”

Harris then colored the ends of the pyramid now sticking out from the rectangle, signaling that this work could be done cheaper with no drop-off in quality.

WORK ON THE MOVE

Harris’ core point is that true transformation requires legal work to move between segments.

Harris then drew a third diagram (labeled “Where the Market Is Headed”) of an upright triangle that reflected where the market was expected to go over the next several years. Pointing to the shrinking extraordinary events market, Harris said, “You can no longer just cruise up here,” citing the relatively recent failure of the law firms Howrey and Dewey & LeBoeuf. (See “Dewey’s Judgment Day,” ABA Journal, February 2015.)

Pressures in the top and middle of the market were catalysts for Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe’s back-office facility in Wheeling, West Virginia, and Fenwick & West’s Flex program, which supplies experienced lawyers as temporary help for legal departments.

Pointing to the bottom of the diagram, Harris continued: “This is the part of the market that is growing,” noting the 50 percent annual growth rate of legal process outsourcers.

Harris said managed services provide a credible way to move to a lower-cost segment without in-creasing risk. A 50 percent savings is possible by moving from Segment 1 to Segment 2 (e.g., moving from a global law firm to a regional law firm). But if you can go from Segment 1 to Segment 3, in which work is performed by technology- and process-enabled contract attorneys, paralegals or foreign lawyers, the savings can be 90 percent.

For this to work, Harris said, a company such as Axiom has to break the linkage between risk and cost. For a huge volume of legal work, a highly pedigreed associate in an elite law firm is no match for a well-designed workflow with standardization, feedback metrics and escalation protocols—procedures that determine when a supervisor has to be called in. When the largest buyers of legal services fully grasp this fact, he predicted, the legal market is going to undergo a massive transformation.

Remember, these comments were made in 2013. According to Harris, Axiom revenue currently is “in the neighborhood of $300 million.” (In November 2016, Harris transitioned from CEO to executive chairman.)

E-DISCOVERY SERVICES

Josh Kubicki, chief strategy officer at Seyfarth Shaw in its Chicago office, says the rise of legal managed services is traceable to the explosion of electronically stored information and to the financial impact of ESI on the cost of litigation.

From 2004 to 2007, Kubicki worked as a regional vice president in the D.C. office of Adecco, a legal temp agency. As the volume of electronically stored information in major litigation continued to skyrocket, law firms discovered that they could hire contract lawyers for as low as $50 per hour and bill them out at rates almost identical to associates. Unlike associates, the cost to pay the contract lawyers stopped when the cases were done.

Kubicki remembers periods when his law firm clients were using hundreds of contract lawyers per day. “Each attorney was generating gross profit of between $20 and $30 per hour,” Kubicki says. “Obviously, that adds up quick.” By 2006, Kubicki’s jobs were generating more than $20 million in revenues.

Illustration by Stephen Ravenscraft.

The growing size and scale of e-discovery engagements eventually led the agencies to start experimenting with what Kubicki calls beta or version 1.0 project management.

“It had become clearer that our clients needed help designing larger-scale solutions,” he says. “That is when I first heard the term managed services. But we didn’t market it that way because, frankly, we already had too much work.”

Around the same time as the financial crisis, corporate clients were wising up to the massive labor arbitrage and began to look for ways to capture some of the cost savings for themselves. This turned out to be a major break for legal process outsourcers.

During this time, David Perla, managing director of investment company 1991 Group, was the co-CEO of Pangea3. Before that, he was an associate at Katten Muchin Roseman in New York City and vice president of business and legal affairs at Monster.com.

“When we started in 2004, we would make a pitch touting our unique combination of cost and quality and got a lot of ‘That’s interesting!’ responses,” Perla says.

Similar to Harris at Axiom, Perla thinks the financial crisis fundamentally shifted the client mindset. “2008 was hands down the best thing ever to happen to the entirety of the industry,” Perla says.

THE STRUGGLE TO KEEP UP

As the “unbundling” movement took hold after the financial crisis, large law firms and lawyers attempt-ed to stay in control by creating their own e-discovery units.

Jeff Brown was among those lawyers. A partner at LeClairRyan in its Richmond, Virginia, office until 2013, he headed the discovery solutions practice and was on the firm’s executive committee. During his last several years there, Brown’s group experienced a relentless decline in the hourly rates clients were willing to pay for document review and e-discovery services typically provided by third-party vendors.

“The only plausible way to keep up was to provide clients with an integrated e-discovery platform, which required an eight-figure investment in technology, process and related resources,” Brown says. “Restrictions against law firms receiving money from outside investors make that option near impossible.”

Brown and other lawyers in his group became advocates of the potential opportunity to transfer more than 400 lawyers and other personnel to UnitedLex to create a new Richmond-based managed services facility.

The transaction eventually obtained full support within the firm, with LeClairRyan signing on as a major UnitedLex client. According to Brown, who was among the lawyers who joined UnitedLex, the per-hour price for document review services has decreased as much as 50 percent since the deal closed.

UnitedLex CEO Dan Reed. Photograph Courtesy of Unitedlex.

This declining cost curve is largely what UnitedLex CEO Dan Reed expected. Reed is a JD-MBA graduate of Vanderbilt University, and he also is a CPA and a former corporate law associate at Greenberg Traurig. In the early 2000s, Reed decided to leave the law to work at Capgemini, a multinational consulting, outsourcing and technology company based in Paris. Capgemini was a pioneer in the IT managed services space. By that time, the managed services playbook was well-developed.

One of the reasons IT managed services took off is that every large business needs high-quality IT support. But each small IT department is a cost center outside the company’s core expertise. By outsourcing information technology, the client gets a much more attractive bundle of services and features. But it also is good for the IT workers, who now have access to better tools and training, a larger group of professional peers, and a career path that provides opportunities to learn and advance.

In 2006, when Reed left Capgemini to start UnitedLex, he could see the clear parallel between information technology and the opportunity to redeploy and retool the growing number of e-discovery experts who work in large law firms. That was only the starting point, as he could see myriad other managed services use cases—data management, contract management, intellectual property—in which a combination of technology, process and business know-how could revolutionize the highly insular corporate legal services market.

Reed says one of the best analogues to UnitedLex is Accenture—but with a core expertise at the intersection of law and business. In fiscal year 2016, Accenture grossed $32.9 billion. Although UnitedLex’s current revenue is between $175 million and $200 million, Reed is not shy about his goal of turning the company into one with several billion dollars in annual revenue.

A FEW WINNERS?

Returning to Harris’ last diagram, it is possible that the largest and fast-growing portion of the legal market, efficiency demand, is going to be dominated by a relatively small number of managed services companies.

If the future plays out this way, it will happen through a massive reallocation of work from law firms and in-house legal departments to companies such as Axiom, Counsel on Call, Elevate, Integreon, Pangea3 and UnitedLex. This market segmentation, as Harris referred to it, will produce the type of deal flow and revenue that will enable investors of several of these companies to exit through an initial public offering.

Cheryl Mason. Photograph Courtesy of HCA.

Although many lawyers would argue such a business structure is impermissible under existing legal ethics rules, we already have an example of a large legal managed services company being owned by public investors: Pangea3, which has been owned by Thomson Reuters since 2010.

At the time of acquisition, annual revenue exceeded $25 million. Since then, “legal managed services have increased in size and seen substantial growth,” says Joseph Borstein, global director at Pangea3.

At least in North America, the revolution in legal services has not waited for the legal regulators. Motivated entrepreneurs and investors have figured out ways to build such companies under the existing regulatory structure. Only now, years later, the practicing bar is beginning to take notice.

STILL BILLABLE

For many years, my writings and discussions with law firms and bar associations have advanced the view that legal innovation requires shifting the risk of cost overruns away from the client to the services provider, primarily by scuttling the billable hour in favor of flat fees.

But as I have researched this story, I gradually have concluded that I was wrong. Legal managed services companies are tremendously innovative. Yet virtually all of them price projects on a per-hour basis.

This mystery started to unravel in a conversation I had with Vince Verna, who became CEO at Counsel on Call in January 2015 after Gridiron Capital obtained a con-trolling interest. Before that, he was an executive in the IT managed services space, most recently at Experis, a subsidiary of the ManpowerGroup, a Fortune 500 company that specializes in human resources.

Verna says that although the managed services model was pioneered and perfected in the IT sector, the playbook essentially works the same way when it is applied to other industry verticals: Create a less expensive, less risky, higher-quality and easier-to-use solution than what your target clients can develop on their own.

“But for this to work as a business, you need volume,” Verna says. “The volume justifies the investment in process, data and technology. Once those systems are in place, you can generate enormous throughput at a very low and predictable cost.”

Although a law firm might laugh at the profit margin of a managed services company such as Counsel on Call, that margin can generate enormous wealth if the services provider can capture, say, 10 to 15 percent of the efficiency demand market.

I had lent Verna my notebook, and he drew three circles—one for law firms, one for legal departments and one for managed services.

“Each group has different core competencies,” Verna says. “But in the legal sector, managed services are just getting off the ground. So over the next several years, the size of this managed services circle is going to grow.”

PROCESS PROS

Vince Verna. Photo by David Mudd Photography.

The distinguishing feature of managed services providers is that they are experts in process, technology and project management. This means they have highly accurate schedules and budgets to price and sell their work.

This core strength is crucial to the business model in ways that go well beyond the client. Specifically, the lawyers who do the work in legal managed services typically are paid by the hour and have no obligation to work beyond a pre-negotiated limit, usually 40 hours or less per week.

The bargain they have struck is a good, professional wage; freedom from business development pressures; and guarantees of flexibility and a work-life balance.

The only way this bargain can be kept is through processes and project management that make the work truly predictable. (One Axiom lawyer, who leads a managed services group in Chicago, quipped, “The faster we get to boring, the better.”) But the balanced workweek is not the only thing that draws experienced and highly specialized lawyers to legal managed services companies.

Over the last year, I have visited managed services facilities at Axiom, Counsel on Call and UnitedLex. In each case, I was struck by the enthusiasm that virtually every lawyer displayed for the team-based environment and an unambiguous goal to continuously improve quality, efficiency and the client experience.

These companies employ several full-time recruiting specialists who cultivate a highly skilled workforce that, in many cases, has become disillusioned with the business practices and lifestyle of large law firms.

Part of the value proposition of a legal managed services provider is a 100 percent alignment of interests between the lawyer and the client—something more important to many lawyers than prestige or money.

The growth potential of the Counsel on Call model became more apparent after talking with Cheryl Mason, vice president of litigation at HCA. She recounted a visit from founder Allen more than 10 years ago—when Mason moved from Los Angeles to Nashville for the HCA job.

“I was frustrated with rising costs and the options we had to manage them. Allen listened very carefully and came up with ideas to truly partner with us,” Mason said.

That conversation eventually led to the creation of Counsel on Call’s first managed services center. Mason handed me a document prepared by Counsel on Call. The first page had a table and a graph that summarized three trend lines from 2008 to 2015.

The first trend line showed a tenfold increase in electronically stored information collected for litigation (from 279 to 2,946 gigabytes).

The second trend line showed progress on data reduction techniques, such as predictive coding and technology-assisted review, moving from 68 to 95 percent, reducing the impact of the massive increase in data subject to discovery.

The third trend line showed a 50 percent increase in total fees billed to HCA for e-discovery.

“This reflects a real solution to my business problems,” Mason said. “I appreciate the metrics, which I routinely share with our general counsel.”

MAKING RAIN

It is hard to get Allen to talk about herself. But if you’re persistent and her team members are present and nudge her a bit, you’ll eventually find strings worth pulling.

One of those strings is the story of how she and her husband decided to seek outside investors. Allen describes a growing feeling that the company was hitting a wall—in terms of capital and the expertise needed to make wise growth decisions. It also was very stressful on her family.

She approached her client advisory board for guidance. “Much to my surprise, one of the members said, ‘You’ve been standing on that windowsill for a long time. It’s time to jump and learn how to fly,’” she said.

Counsel on Call eventually settled on Gridiron Capital, largely because “it was the only firm that was truly interested in our lawyers.” This values alignment was crucial to Allen.

Before they would close the deal, Gridiron Capital requested “net promoter” data from Counsel on Call clients. This is a common metric used by corporate America to measure customer satisfaction. It typically asks, “How likely is it that you would recommend [us] to a friend or colleague?” Zero is not at all likely; 10 is extremely likely.

According to legal ethics specialist Pera, Counsel on Call clocked in at a phenomenal 9.8.

Wondering which two clients thought they did not receive level-10 service, Allen followed up. One of them confided that they were actually very satisfied. But in the legal field, “a 10 is a unicorn. It really doesn’t exist.”

Professor William D. Henderson is the Val Nolan faculty fellow at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Lawin Bloomington. This article originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of the