Second Lives: For These Former Justices, Retirement Is No Day at the Beach

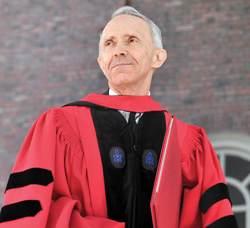

Former Justices David H. Souter, Sandra Day O’Connor and John Paul Stevens (above), since stepping down from the Supreme Court, have served on federal appeals court panels, given interviews and made opinionated speeches on recent decisions.

When Justice John Paul Stevens stepped down from the U.S. Supreme Court last year, it marked the first time in 12 years that there have been at least three retired justices.

And going back to 1994, when Justice Harry A. Blackmun retired, there began a period of a little more than a year when five ex-justices were still puttering around—former Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, and former Justices Lewis F. Powell Jr., William J. Brennan Jr. and Byron R. White.

But with a few exceptions, those justices were largely out of the spotlight in retirement.

For the three current ex-justices, retirement has seen little in the way of shuffleboard, Mahjong or Caribbean cruises. Instead, Justices Sandra Day O’Connor, David H. Souter and Stevens have been rewriting the book on retirement pursuits and expectations.

“Until now there wasn’t much post-judicial behavior” for retired justices, says Linda Greenhouse, who covered the Supreme Court for the New York Times for some 30 years and is now a senior research scholar and lecturer at Yale Law School. “Those who weren’t carried out were pretty old and debilitated by the time they left the court. Now we have this unusual collection of energetic, very engaged individuals.”

BREAKING THE MOLD

Of the 103 former justices, 49 remained on the court until they died, and many left in poor health, Greenhouse notes. Others left for specific reasons. John Jay, the first chief justice, once called the post “intolerable” and ran for governor of New York. President Lyndon B. Johnson talked Justice Arthur J. Goldberg into leaving the court in 1965 to become United Nations ambassador. Burger stepped down after 17 years to lead the bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution.

But few can recall such an outspoken trio as these. For Stevens, 91, a two-week period in May was emblematic. In a May 2 speech in New York City, he criticized his ex-colleagues for overturning a damages award for a man who spent 14 years on death row because prosecutors failed to turn over exculpatory evidence in a murder case. Referring to a March 29 concurrence by Justice Antonin Scalia in Connick v. Thompson, Stevens said, “Justice Scalia has either overlooked or chosen to ignore the fact that bad faith, knowing violations” of a rule requiring such disclosures of evidence “may be caused by improper supervision” in a prosecutor’s office.

The next day, in another speech, the retired justice said he would have joined the lone dissent of Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. in Snyder v. Phelps, where the court held that the First Amendment shields members of the Westboro Baptist Church from tort liability for picketing the funeral of an American serviceman.

“It might interest you to know that if I were still an active justice, I would have joined [Alito’s] powerful dissent,” said Stevens. “To borrow Sam’s phrase, the First Amendment does not transform solemn occasions like funerals into ‘free-fire zones.’ ”

Just a few days later, on May 12, Stevens weighed in on the U.S. mission that killed Osama bin Laden. Speaking at a symposium at Northwestern University Law School about his 35-year tenure, Stevens noted that there had been “some debate about the propriety” of the killing of bin Laden by U.S. Navy Seals.

“I must say I was proud of the Seals,” said Stevens, a Navy codebreaker during World War II and the last veteran of that war to serve on the high court. “It was not merely to do justice and avenge Sept. 11. … It was to remove an enemy who had been trying every day to attack the United States.”

“It seems clear that Justice Stevens wants to speak out on issues that are quite important to him,” says University of Georgia School of Law professor Diane Marie Amann, a former Stevens clerk. “What’s remarkable is that he has been speaking to groups that he never spoke to [while serving on the court], and he’s been putting together remarks that have been tailored to the interests of that group.”

She notes that besides his speeches, which included one last fall addressing the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, Stevens is completing a book about the five chief justices he has known either as a law clerk or as a justice.

Stevens told author Bill Barnhart in a recent interview in The Atlantic that he had no desire to linger on the court beyond his physical prime. Stevens recounted that he had secretly asked Souter a few years ago to tell him when it was time to go. When Souter retired in 2009, “I knew I didn’t have any safety valve anymore,” Stevens said in the interview, adding that he decided he would retire (at term’s end) the day in January 2010 when he faltered in delivering his dissent from the bench in the campaign-finance case Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, photo by Leigh Vogel/Getty Images.

O’Connor, 81, has been active in a number of causes since she left the bench in early 2006, notably her campaigns in favor of merit selection of state court judges and work to improve civic education. O’Connor, who travels and speaks frequently at a wide variety of events, has sometimes made tart comments on issues of the day. Last year, at a symposium at the College of William & Mary law school, O’Connor said she regretted that some of her decisions on abortion rights, campaign finance and race-conscious government policies were “being dismantled” by the current court.

“What would you feel?” O’Connor was quoted in USA Today. “I’d be a little bit disappointed. If you think you’ve been helpful and then it’s dismantled, you think, ‘Oh, dear.’ But life goes on. It’s not always positive.”

Souter, who retired in 2009 and will turn 72 in September, is less visible than his fellow ex-justices. But he has hardly been a recluse. Like O’Connor, Souter has served by designation on federal appeals court panels, and he even wrote the decision in a case last year. (Stevens has not yet served on any appeals panels.)

The usually media-shy Souter even gave an interview to 60 Minutes last year, in tribute to Stevens.

In 2010, Souter delivered a speech at Harvard University’s commencement that offered a critique of originalist interpretations of the Constitution, which the retired justice called the “fair reading model.” Several liberal commentators lauded his discussion of the need for justices to go beyond the plain text to make choices among the competing values in the Constitution.

“The Constitution is a pantheon of values,” Souter said, “and a lot of hard cases are hard because the Constitution gives no simple rule of decision for the cases in which one of the values is truly at odds with another.”

Artemus Ward, an associate professor of political science at Northern Illinois University who has written about the timing of high court retirements, believes all three retired justices chose to step down when they viewed the political conditions as favorable for selection of their successors.

“This also means they can be more active in retirement,” Ward says. “And in retirement, one also wants to continue to spin the record and influence a favorable historical judgment on [one’s tenure].”

Justice David H. Souter, photo by AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta.

Amann and Greenhouse agree that many retired justices have sought to burnish their legacies. The more active models of retirement displayed by O’Connor and Stevens, and to a lesser extent by Souter, can only help engage the public about the Supreme Court.

Amann, who is writing a book about Stevens, doesn’t consider any of the retired justices’ comments to have crossed a line into outright criticism of their former colleagues. “Each of them has chosen a path that is extremely respectful of their peers on the court,” she says.

Greenhouse adds that with the active paths chosen by court retirees, the public gets “the unconstrained benefit of their experience and they don’t have to filter it through the usual constraints of sitting judges. I just think that adds something to the public discourse about the court.”