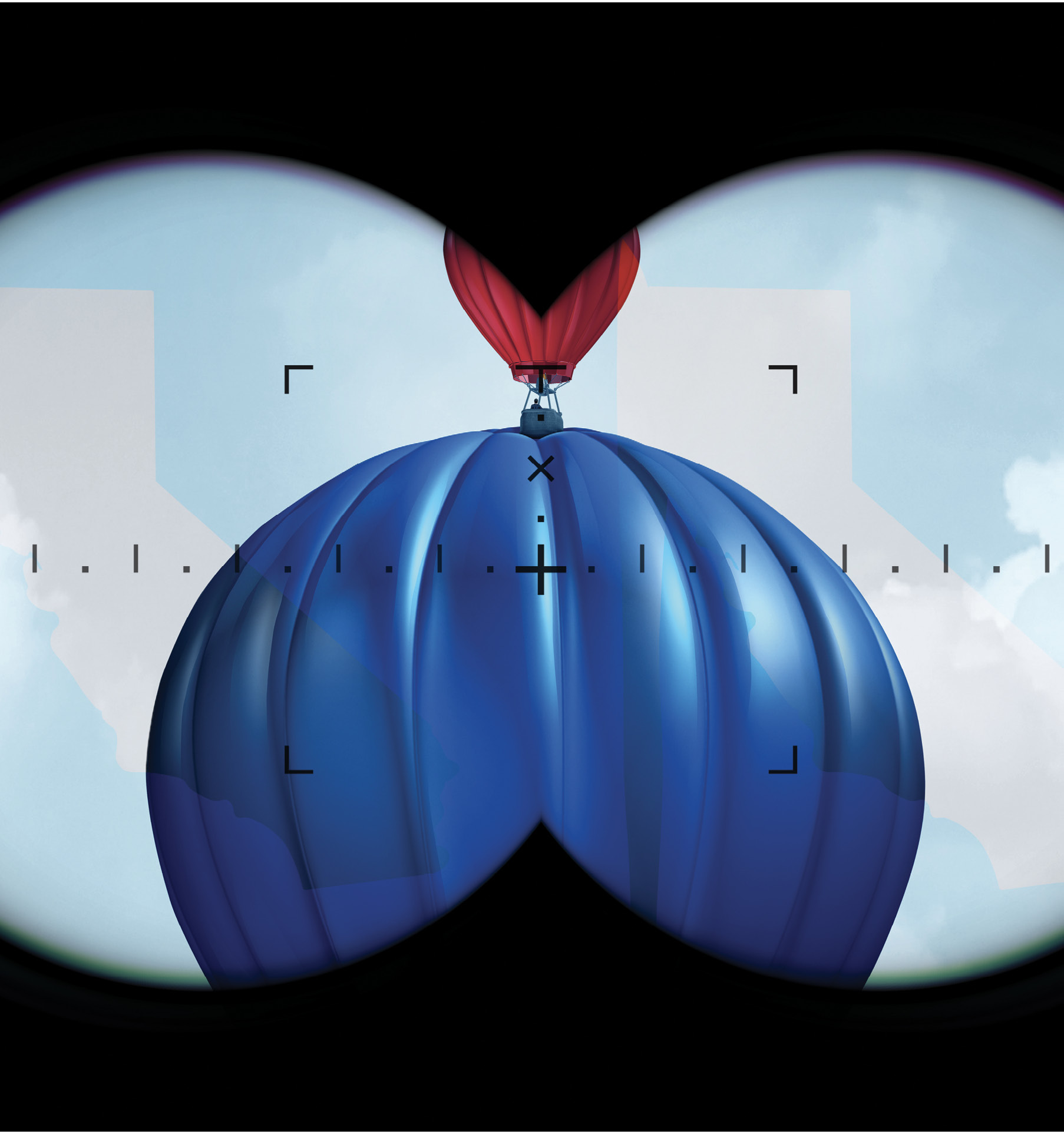

States are quietly stepping up antitrust enforcement to ensure fair competition

States are quietly stepping up antitrust enforcement. Photo illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock.

In September 2022, California Attorney General Rob Bonta sued Amazon, alleging the com- pany’s pricing policy for third- party merchants undermines competition and raises prices for consumers elsewhere.

The suit, filed in state superior court, claims that in order to sell through Amazon, everyday sellers must sign agreements that they won’t charge lower prices on competing e-commerce sites such as Walmart’s. If they violate the contracts, the sellers face less prominent placement and even risk getting booted from selling new wares on Amazon, according to the suit.

“We won’t allow Amazon to bend the market to its will at the expense of California consumers, small-business owners, and a fair and competitive economy,” Bonta said in a statement. Amazon has argued its policy simply ensures consumers pay less on its own site.

As Big Tech companies like Amazon and Google have come under scrutiny in recent years for their economic power, antitrust challenges are no longer being driven just by players in the federal government. As in California, the states are now coming for the companies too.

States are armed with a new power that means companies in tech and beyond will have to spend more time looking over their shoulders, legal observers say. Congress slipped a measure known as the State Antitrust Enforcement Venue Act into an omnibus bill that became law at the end of 2022. The measure prevents antitrust lawsuits brought by state attorneys general from being consolidated against their will with complaints from other private antitrust plaintiffs for pretrial proceedings—a power federal enforcers already had.

Such consolidations usually mean states’ cases get transferred away from courts of their choosing. And now that states are able to go it alone, they won’t have to hash out tactics and compare schedules with private plaintiffs who haven’t had the benefit of subpoenas to dig around as deeply as states can before filing complaints. State attorneys general, who usually hope to get quick redress, also may know the leanings and interests of “their” federal district judges better than tech companies’ corporate counsels.

“States are known to hunt in packs, but they are increasingly breaking off the pack to bring their own cases,” James Lloyd said at the ABA’s 2023 Antitrust Spring Meeting in March. Lloyd is chief of the antitrust division at the Texas attorney general’s office.

Effects of new power

Businesses now need to pay more attention to state attorneys general, says attorney Mark Herring, who served as Virginia’s attorney general for eight years until 2022 and is now a partner with Akin Gump in Washington, D.C.

“There are going to be a lot more microscopes on corporate activity,” Herring says.

As a result, legal experts say companies and the lawyers defending them will be dealing with more and faster pretrial processes—as well as potentially divergent rulings about discovery, summary judgment and more.

Defense attorneys might be less pleased with these changes, according to Milton A. Marquis, a shareholder in the Washington, D.C., office of Cozen O’Connor.

“From a defense perspective, there was a great deal of efficiency and fairness to having a single jurisdiction handle these legal issues,” Marquis says. “I can’t imagine that, in a typical case, a defendant would prefer litigating a state AG case in court X and everyone else litigating in court Y.”

Companies and judges have argued that courts may have to hear disputes that other districts have already disposed of; communications deemed privileged in one matter might get made public under rulings in another; and, overall, it could make the administration of justice costly.

“Given the nationwide scope of these antitrust litigations, such inconsistent rulings may complicate proceedings and sow confusion not only among the courts and parties, but also in the marketplace,” Judge Roslynn R. Mauskopf, director of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, wrote in a 2021 letter to Congress.

But Marquis—who has worked in the federal government as well as for the attorneys general of Massachusetts and Virginia—is one of many who say the new law allowing states to stay in their preferred venues likely means swifter resolutions, which could lead to rushed judgments.

Marquis points to a massive, evolving multidistrict antitrust litigation against generic drugmakers as an example of what the new law could expedite: The matter is still pending in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania despite states having sued in 2016. Although it’s a complex case, Marquis estimates it might have taken as little as two years to resolve if states were the only plaintiffs.

“You’re talking about a substantially less-protracted litigation,” he says.

Lawyers are watching

Law firm practices and in-house counsel focusing on states have become more common. In addition to Akin Gump’s hiring of Herring, Bloomberg Law reported in 2021 that DLA Piper, Jones Day and Crowell & Moring had expanded or started up practices specializing in state attorneys general.

Former Washington, D.C., Attorney General Karl Racine, who sued Amazon in addition to other tech companies during his tenure, joined Hogan Lovells in January to start its state-focused practice, and many other firms have lawyers embedded in competition or consumer protection practices with an expertise in state issues. These lawyers keep tabs on the public speeches, writings and complaints of 56 state and territorial attorneys general and their antitrust staff members.

“It has really taken the attention of the corporate world,” says Jeff Tsai, a former top adviser to then-California Attorney General Kamala Harris. Tsai now co-chairs global firm DLA Piper’s state attorneys general practice. “They have sat up and stiffened their spines in reaction to AGs—such as the one in Washington, D.C., or the one in Texas, or the one in California.”

Pendulum has swung

The debate about the proper scope of enforcers’ powers in competition law comes as antitrust has become a popular topic on both sides of the political aisle and even outside of the legal world.

Antitrust has come up in recent presidential campaigns, and Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan—an eager enforcer and corporate antagonist—has been the subject of coverage in major media.

Khan and others say that they’re trying to revive antitrust enforcement, which they contend withered in the past 40 years as influential legal scholars followed laissez-faire economic theories that suggested true antitrust violations were rare.

The U.S. Supreme Court followed suit, with big wins for corporate defendants in cases such as Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko in 2004. In that dispute, a law firm filed a class action claiming that the phone carrier’s discriminatory treatment of some local competitors’ networks and those networks’ customers violated antitrust laws. The high court took the opportunity in its decision to narrow its jurisprudence on when firms have to share their own property as a way to ensure competitive markets.

Plenty of traditionalists and longtime practitioners still do dismiss trends of wider antitrust enforcement led by figures like Khan. They say it’s a threat to innovation that results in enforcers inventing legal theories to punish disfavored corporations.

Looking ahead

At least one state, Minnesota, is looking at adding an abuse of dominance standard that would allow the state to go after companies with higher market share.

New laws could mean problems for Google as well as Meta, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and others.

However, it’s not certain that interest in antitrust will result in a newly empowering legal environment for enforcers, says Trish Conners, a shareholder at Stearns Weaver Miller in Tallahassee, Florida, who spent 36 years in the antitrust section of the Florida attorney general’s office.

“There’s still a conversation about whether or not this is a momentary blip,” she says. A Republican presidential administration could pull back, she notes, or judges might slap down the theories that enforcers are experimenting with.

Ultimately, though, she doesn’t think states will back down.

“For the states, whatever happens at the federal level doesn’t really put the genie back in the bottle,” she says.

This story was originally published in the October-November 2023 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Antitrust Busting: States are quietly stepping up enforcement to ensure fair competition.”

Ben Brody is a longtime Washington, D.C.-based policy and politics reporter.