Successful ballot measures for marijuana and other drugs create opportunities for lawyers

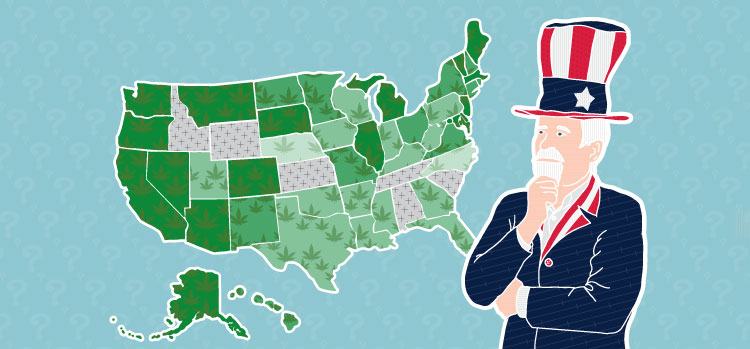

Illustration by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal

The 2020 electorate was one of the most polarized in recent memory, with red state and blue state voters hunkering down on each side. But despite the partisan rancor, there was one topic that solid majorities of voters in both camps were able to agree on: drugs.

Voters from politically blue New Jersey to deep red Mississippi and South Dakota were among those passing ballot measures that will loosen state laws around marijuana. With this recent green wave of approvals, an estimated one in three Americans now lives in a state with legalized recreational marijuana. Others are in states with medical marijuana. And in some places, citizens went even further, voting to relax laws around psilocybin—or psychedelic mushrooms—and even decriminalize the possession of small amounts of harder drugs such as cocaine.

The widespread embrace of substances that just a few years ago could get a person tossed in jail or ruin a career—and in some states, they still can—is encouraging a whole new crop of lawyers to support the legal drug industry. And on the criminal side, the growing acceptance of marijuana and other drugs is adding momentum to the expungement movement.

Whether it’s advising a cannabis business on how to comply with state and local regulations or helping a person clear an old drug-crime record, lawyers say practicing in this space can be both exhilarating and frustrating.

“This is going to create a whole new slew of problems, and how do I help fix that?” asks Whitney Hodges, a San Diego-based real estate and land use attorney in Sheppard Mullin’s cannabis practice. These businesses have a wide range of legal needs, from tax and regulatory issues to land use and intellectual property protection, she says.

Even before the November election, the trend was moving toward legalizing marijuana. The election kept that momentum going, resulting in a total of 15 states where voters have either enacted or voted in favor of enacting adult recreational use and 36 states that have done the same with medical marijuana, according to the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. Here’s what passed:

• In Mississippi and South Dakota, voters approved the legalization of medical marijuana.

• In Arizona, Montana and South Dakota, voters legalized possession and cultivation of marijuana by adults for personal use and backed the establishment of a regulated retail market.

• In New Jersey, voters approved a public ballot question legalizing cannabis; the state assembly then passed two bills that Gov. Phil Murphy had not signed at press time.

• Voters in Oregon approved the legalization of psilocybin for supervised mental health treatment, and District of Columbia voters approved decriminalizing mushrooms and other psychedelic substances such as ayahuasca and peyote.

• Also in Oregon, voters backed decriminalizing the possession of small amounts of hard drugs like cocaine, heroin, oxycodone and methamphetamines, and supported using sales tax from previously legalized marijuana to help pay for addiction treatment instead of sending users to jail.

Lawyers’ role

Like any nascent industry, legal marijuana needs lawyers. But what’s tricky—and exciting for lawyers who are up for a challenge—is it’s highly regulated at the state level but still illegal at the federal level. Marijuana is a Schedule I drug under the federal Controlled Substances Act, a category that includes heroin and ecstasy. In 2019, the ABA passed a resolution calling for marijuana exemptions from the act as well as legislation to support cannabis research.

The tension between federal and state law “is a big part of why I have a job and why I am so busy,” says Alison Malsbury, the San Francisco-based co-chair of Harris Bricken’s corporate practice group, who applies her intellectual property law knowledge to the booming cannabis industry. “We really have very little caselaw to rely on in many areas of cannabis law.”

Colorado was one of the first two states to legalize recreational marijuana in 2012. And Denver-based attorney Bob Hoban was there at the beginning, using his background as a commercial litigator to help usher in the legal cannabis industry. He helped formulate the state’s regulations and now runs a global law firm that assists hemp and marijuana companies.

Hoban Law Group provides regulatory assistance, tax and banking advice, intellectual property protection, litigation services and more. Firms such as his offer legal services to an industry that just a few years ago was more likely to need a criminal defense attorney than a business lawyer. Hoban says every day brings a new legal challenge.

Hoban was drawn to the industry after his mom fell ill with pancreatic cancer in early 2005. Initially, she was given just six months to live, and between rounds of chemotherapy, her doctors prescribed opiates, which brought their own problems.

Looking for a better way, Hoban tried a piece of a cannabis-infused candy to test its effects, then he gave his mom a small bite to see if it would help.

It worked wonders, he says. Her appetite returned, and eventually she was able to get off the addictive pills. She lived another 3\0xBD years with an improved quality of life, and Hoban says he became convinced of cannabis’ medicinal value.

A federal-state divide

But despite broad national support and the legal cannabis industry representing an estimated $13.6 billion in the United States in 2019, the unresolved tension between federal and state law has a host of implications, from banking to taxes to land use for the businesses that grow and sell marijuana.

Lawyers practicing in this area can find themselves in ethical minefields. All attorneys are duty-bound to not assist a client in violating the law, but growing and selling marijuana is illegal under federal law.

Bar associations typically say that if lawyers disclose this, they are operating ethically, Malsbury says. The ABA’s House last year adopted resolutions calling on Congress to clarify that it’s not a federal crime for lawyers to take on cannabis clients or for banks to provide services to cannabis lawyers if they are acting in accordance with state law.

“The cannabis industry is just like any other industry, except for so many years it was completely illegal,” says Sarah Blitz, a Los Angeles-based business and commercial litigator with Sheppard Mullin’s cannabis team.

Blitz and her colleagues say the very first conversation they have with new clients is to remind them marijuana is still illegal under federal law, and then they devise a strategy to navigate the legal divide.

For example, in the area of intellectual property law, companies are able to get federal patents for their plant clones or product recipes. But they can’t federally trademark their cannabis products. So they may decide to trademark something related, such as a clothing line.

Interstate and international movement of goods is another troublesome spot. It’s why Dean Heizer, executive vice president and chief legal strategist at Denver-based LivWell Enlightened Health, is hoping marijuana eventually will be legalized nationwide so the U.S. can catch up with its neighbors. Mexico’s Senate approved a cannabis legalization bill in November; Canada approved adult use in 2018.

“Can I speak frankly? This is all stupid,” Heizer says. “The drug is in every country on the planet, and it’s used with minimal ill effect across the world.”

One hope for resolving some of the federal vs. state legal conundrum is a bipartisan proposal in Congress called the Strengthening the Tenth Amendment Through Entrusting States Act, which would prevent federal interference in states, territories or Native American jurisdictions that already have legalized cannabis and have a robust regulatory system. Proponents say this hands-off approach would correct problems with federal banking and tax laws and help draw investor capital without having to legalize marijuana nationally.

Expungement efforts

Meanwhile, in December the House passed the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act, which would remove pot from Schedule I and facilitate the expungement of past minor drug convictions as well as tax cannabis products to fund criminal and social reform projects.

Supporters of expungement say old criminal records can keep people from getting jobs, student loans and housing, arguing people deserve a fresh start, especially in states where pot is now legal anyway.

Maritza Perez, national affairs director for the Drug Policy Alliance, hopes the continuing acceptance of cannabis—and now in some places, mushrooms—will result in more vigorous efforts to right what she says are past wrongs.

Once drugs are legalized in a state, “you can’t just pretend that the past harms don’t exist and don’t affect people’s lives today,” Perez says.

Some of that work is done by nonprofit legal aid clinics. And some corporate cannabis attorneys want to help: Hoban’s firm is already doing pro bono work on expungements, and Hodges says the team at Sheppard Mullin is exploring volunteer possibilities.

Law schools also are offering classes specifically in cannabis law, touching on the broad implications for the new field.

Hoban says it’s a lot of pressure and responsibility working on this legal frontier. But he adds, “I’m proud of it. And I know my mother would be really proud of it.”

This story was originally published in the Feb/March 2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “A Green Wave: Successful ballot measures for marijuana and other substances create opportunities for lawyers”