Justice Breyer says looking to international law can help the court evaluate US cases

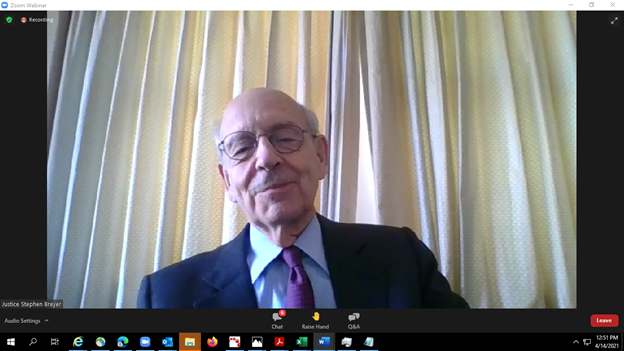

Stephen Breyer speaks at the ABA International Law Section’s 2021 Virtual Annual Meeting.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer told the ABA's International Law Section on Wednesday that his court will continue its recent trend of looking to overseas legal authorities and briefs from foreign interests as it weighs cases with worldwide implications.

“We, in doing our job, I think have no choice in that,” said Breyer, speaking remotely as the keynoter on the first day of the International Law Section’s 2021 Virtual Annual Meeting. “You can’t do your job properly without [looking to international law] in some cases, and it’s a growing number. I’d say quite a few now. You have to know something about and look for something beyond your own shores.”

Breyer is this year’s recipient of the International Law Section’s World Order Under Law Award, which is given to individuals who have made a substantial contribution to and provided visionary leadership in pursuit of the ABA’s Goal IV: to advance the rule of law in the world.

“You are a very strong supporter and believer in the rule of law,” said Salli A. Swartz, the moderator of the 40-minute conversation with the justice. Swartz is a past chair of the International Law Section and a co-founder of Artus Wise Partners, a Paris-based law firm.

“The rule of law internationally these days is not a pretty sight,” Swartz observed.

Breyer said that courts, whether in the United States or elsewhere, must convince the citizens of their nations that they are following the rule of law and not acting arbitrarily.

“The arbitrary easily shades into the autocratic,” Breyer said. He recalled a visit from the head of the Supreme Court of Ghana, who asked, “Why do people do what you say?”

The persuasive power of U.S. courts “has grown gradually over time until it’s become like the air that you breathe,” Breyer said. “We have to keep convincing, not the few thousand or so … who are judges, and not the million or so who are lawyers, but the 299 million or more that are not lawyers. They have to understand why it is important to follow a decision they really don’t like.”

Swartz advised participants that the conversation with the justice would not be veering into such hot-button topics as “court-packing,” age limits for justices, or any impending retirements—“mine, the justice’s, or anyone else’s.”

“If you’re looking for a scoop, this is not the call,” she said.

Swartz referred participants to Breyer’s two-hour speech to Harvard Law School last week in which the 82-year-old justice argued that public trust in the court rests on a public perception that “the court is guided by legal principle, not politics” and that such trust would be eroded if the court’s structure were changed in response to concerns about the influence of politics on the Supreme Court.

People “whose initial instincts may favor important structural … changes, such as … ‘court-packing’” should “think long and hard before embodying those changes in law,” Breyer said in the Harvard speech.

Breyer did not address, either in his Harvard speech or his remarks Wednesday before the ABA group, calls from many on the left that he retire this year when President Joe Biden and a Democratic-majority Senate could replace him with a younger progressive.

At the International Law Section event, Breyer said he is sometimes struck by the number of cases on his court with international implications, with amicus briefs from foreign governments, regulators or other international bodies.

Referring to a 2013 copyright case involving cheaper foreign editions of textbooks that a Thai national was offering for sale in the United States, Breyer told the conference he was surprised by the large number of briefs.

“Toward the end of the pile, I see why,” Breyer said. “We’re told by some group that should know that [our] decision is going affect more than $3 trillion worth of commerce. That is the world, and we’re part of that.”

Breyer wrote the opinion for the court in Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons Inc., which largely ruled for the student.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Breyer has been one of the court’s most active participants in remote speaking engagements over Zoom and similar platforms. On Wednesday, in the minutes before the luncheon session began, the justice could be heard quieting his grandchildren.

Swartz, a dual citizen of France and the United States, closed by asking Breyer, a noted Francophile, about the role of dissenting opinions, given that French appellate courts do not issue them.

Breyer said dissenting opinions in the Supreme Court play a valuable role. The first role is during internal debate, to try to convince the majority to “flip,” but that is rare, he said. The second role for the dissent is to prompt some changes in the majority opinion, or at least make the majority answer the concerns raised.

“In this, [the dissent] almost always succeeds,” Breyer said.

A third role is to try to lay a foundation for a future direction of the law, he said.

“The worst reason to publish a dissent, though I can’t say it doesn’t happen even with me, too, is, ‘Well, I wrote it. The world might as well benefit from it.’” Breyer said.