Student free speech case 'chipped away' at after 50 years, but 'overall idea' remains

March 4, 1968, in Des Moines, Iowa: Mary Beth Tinker and her brother John display two black armbands, the objects of the U.S. Supreme Court’s agreement to hear arguments on how far public schools may go in limiting the wearing of political symbols. The children, both students at North High School, were suspended from classes along with three other students for wearing the bands to mourn the Vietnam war dead. Bettman via Getty Images

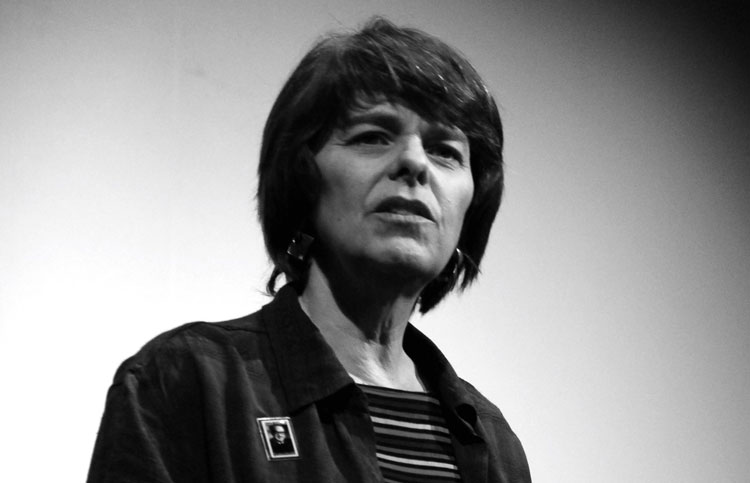

Mary Beth and John Tinker remain as engaged and committed to young people’s free-expression rights as they were more than 50 years ago when they were suspended from their middle and high schools in Des Moines, Iowa, for wearing black peace armbands.

The siblings—along with the now-deceased Christopher Eckhardt—wore the armbands to protest the Vietnam War, support Robert Kennedy’s Christmas truce and to mourn those who had perished in the conflict. School officials reacted with a quickly enacted policy that prohibited the wearing of armbands. Officials passed this policy targeting this particular symbol, even though students still were allowed to wear political campaign buttons and Iron Crosses.

The students wore the armbands anyway and faced suspensions. The Tinkers believed passionately in their right to dissent from a war they felt was unjust. “When we were told that we would not be allowed to express our opinion about the war in this purely nonviolent and nondisruptive way, we felt that there had been an offense against a principle that we were obligated to try to defend,” John Tinker says.

They lost before a federal district court, and a split ruling from the St. Louis-based 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals meant that their only avenue of relief was the court of last resort. But the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in favor of the students in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District. It remains the leading student speech decision even today.

Photo of Mary Beth Tinker by Andrew Imanaka

“Tinker was hugely important—I’d say it is the most important student speech case the Supreme Court ever decided,” says professor Emily Gold Waldman of Pace Elisabeth Haub School of Law, who has written extensively about student speech issues. “The Supreme Court explicitly held that students have free speech rights at school—that those rights don’t stop ‘at the schoolhouse gate’—and that those rights are fairly expansive. I also think it’s relevant that the Tinker court recognized that one of the purposes of schools is ‘personal intercommunication among the students’—that such communication isn’t just inevitable, but it’s actually desirable and educational.”

“It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech and expression at the schoolhouse gate,” Justice Abe Fortas wrote for the majority. “Undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance is not enough to overcome the right to freedom of expression.”

Fortas’ opinion reads like a paean to the importance of freedom of speech and education in a democracy. “In our system, state-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism,” Fortas wrote, and students are full persons within the meaning of the Constitution.

“So much of the Fortas ruling is a great description of what education should be in a democracy,” says Mary Beth Tinker. “I always recommend it to students and teachers, and I particularly like the part about students being ‘persons,’ with the rights and responsibilities of persons. There’s nothing better than telling a big crowd of high school students in an auditorium that the Supreme Court has ruled that they are, in fact, persons.”

Before the Tinker decision, those in public education did not really know the extent of student free-speech rights. The court had issued its famous decision on Flag Day in 1943 in West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, declaring that two sisters who were Jehovah’s Witnesses could not expelled for refusing to salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Justice Robert Jackson wrote eloquently about the need for school officials to respect student rights and “not to strangle the free mind at its source and teach youth to discount important principles of government as mere platitudes.” However, Jackson and his colleagues did not create a test or standard for when student speech was protected.

But Justice Fortas looked to decisions in the 1960s from the New Orleans-based 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals involving African-American students wearing “freedom buttons” at their all-black schools to protest voting discrimination. The 5th Circuit had said that at one school in Philadelphia, Mississippi, school officials had punished students without any showing that the freedom buttons would cause a substantial disruption of school activities.

Burnside v. Byars proved pivotal to Justice Fortas, who wrote that public school officials could only prohibit or censor student speech when they could reasonably forecast that the student would cause a substantial disruption or material interference with school activities or invade the rights of others.

Photo of Mary Beth Tinker by Eli Hiller/Wikimedia Commons

“The civil rights aspect of the case was very important to us, as a family, at the time,” recalls John Tinker. “Our armband protest was motivated by an awareness of the suffering due to the war in Vietnam. But even prior to that, we—as a family—had been and continued to be part of the nonviolent civil rights movement that was focused on racial discrimination.”

Justice Hugo Black, normally known as a First Amendment defender, wrote a passionate dissent in Tinker warning that the decision would usher in a “revolutionary era of permissiveness.” The decision certainly led to students challenging more school policies, ranging from the censorship of school newspapers and dress code restrictions.

In later years, a more conservative U.S. Supreme Court created exceptions or carveouts to the Tinker ruling for student speech that was vulgar or lewd in Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986); for school-sponsored speech that school officials had a legitimate reason to regulate in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988); and student speech that school officials reasonably believed promoted the illegal use of drugs in Morse v. Frederick (2007).

“When a student speech case doesn’t fall into one of those buckets—and many such cases don’t—then Tinker applies,” Waldman says.

“It’s upsetting to see how the Tinker ruling has been chipped away, but the overall idea of Tinker remains: that young people do have free speech rights in school and that their input and humanity should be respected,” Mary Beth Tinker says.

In recent years, there has been a rise in student activism and assertion of First Amendment free-speech rights. This pleases the Tinkers immensely.

“Seeing the increase in youth speaking up for their own interests is so heartening to me,” Mary Beth Tinker says. “As a nurse, including as a trauma nurse and ER, I have worked mostly with young people. I have seen firsthand how youth pay for the price for policies that do not make their interests a priority. In the areas of health, housing, education, the environment, economics, racial justice, criminal justice, education, young people have very little say, but they are greatly affected.”

“If there is a student who has been encouraged by my story to have a voice and to stand up for their beliefs, I am very happy,” says Mary Beth Tinker. “The great privilege of my life has been to spend it with young people and those who care about their well-being.”

David L. Hudson Jr. teaches at Belmont University College of Law.