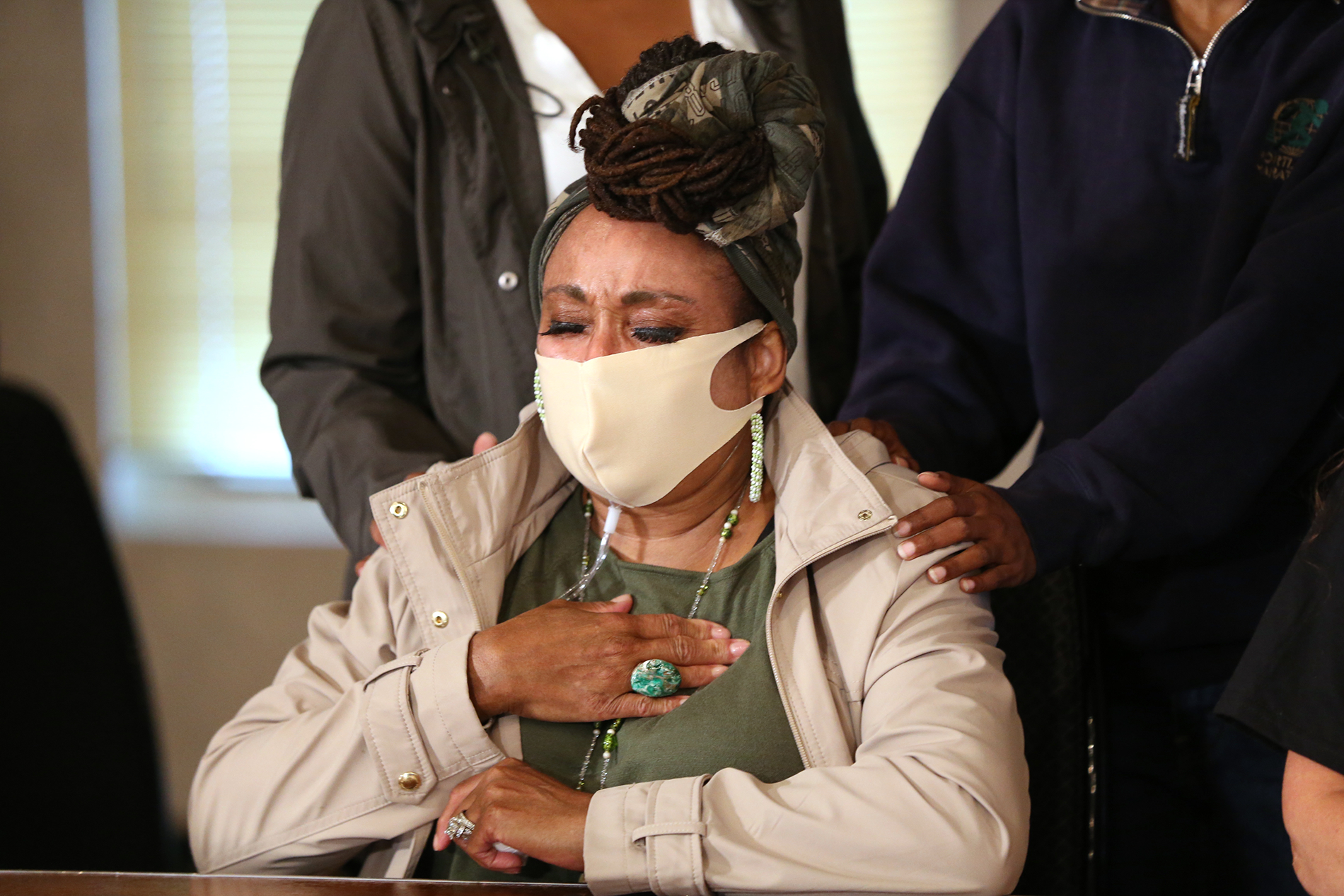

In October 2023, three Tacoma, Washington, police officers went on trial for the 2020 death of Manuel Ellis, a Black man who died after he was punched, put in a chokehold and tased during a confrontation with police. In December, a jury acquitted the officers of second-degree murder and manslaughter.

One detail in the defense’s case may have influenced the jury: A paramedic at the scene testified that he believed Ellis showed signs of “excited delirium”—a controversial diagnosis that law enforcement agencies and some medical examiners use to describe a dangerous, agitated condition often brought on by drug use. Critics, however, say that excited delirium is pseudoscience that’s been used for decades to excuse deaths in police custody.

Though the Pierce County medical examiner described Ellis’ death as a homicide caused by hypoxia due to restraint, the defense pointed out that Ellis had methamphetamines in his system to make the case that excited delirium might have been to blame rather than excessive police force.

But critics say excited delirium is pseudoscience that’s been used for decades to excuse deaths in police custody.

Organizations, including Physicians for Human Rights, argue that excited delirium has no medical foundation and that its origins are plagued with racism. The term’s role in high-profile police misconduct cases, including the deaths of Ellis, Elijah McClain, and George Floyd has prompted major medical organizations to repudiate its use.

In October, California became the first state to ban the use of excited delirium as a cause of death in medical examiner reports—prompted by the 2021 death of Angelo Quinto, a Filipino American veteran who was experiencing a mental health crisis and died after police kneeled on his back for five minutes. Medical examiners described the cause of death as excited delirium, and a later coroner’s report called the death an accident rather than a homicide.

Roger Mitchell, a professor of pathology at Howard University, says excited delirium should not be used as a cause of death because it includes a constellation of symptoms but no pathophysiological mechanism. “It’s not specific in all the symptoms that have been attributed to it,” Mitchell said. “You can have all or you can have none. At the end of the day, the mechanism that leads to death is often either cardiac, respiratory, or metabolic.”

In 2020, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) issued a statement saying it does not recognize excited delirium as a mental disorder, and in 2021, the American Medical Association stated that excited delirium is not an official diagnosis. The National Association of Medical Examiners followed suit in 2023, stating it should no longer be cited as a cause of death. The APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has never recognized excited delirium, but does list “delirium, hyperactive type,” a more limited and specific diagnosis.

Others, however, such as James Gill, Connecticut’s chief medical examiner and author of a 2014 paper describing excited delirium as a valid diagnosis, believe that a life-threatening condition—often involving drug use—exists and can result in paranoid, agitated and violent behavior that needs medical terminology to describe it.

Gill notes that stimulants, such as cocaine and methamphetamine, can produce a surge in adrenaline and other hormones, which can lead to a surge in blood pressure, an irregular heartbeat, and in some cases, death. “Sometimes that happens before the police ever show up,” Gill says. “Sometimes it happens while the police are subduing the person. Sometimes it happens in the emergency room or the ambulance.”

The American College of Emergency Physicians—whose policies inform decisions made by paramedics and first responders—published a controversial 2009 paper that was often used to allow court testimony in favor of excited delirium.

But in 2023, after a grassroots effort by some members, the organization dropped its endorsement of that paper, noting “ACEP’s 2009 White Paper Report on Excited Delirium Syndrome is outdated and does not align with the college’s position based on the most recent science and better understanding of the issues surrounding hyperactive delirium.”

According to ACEP board chair Jeffrey Goodloe, the physicians organization prefers to use a more specific, limited and accepted diagnosis—hyperactive delirium with severe agitation. “Despite good intentions of the 2009 paper,” Goodloe says, “there perhaps was not enough emphasis on the importance of everyone—from law enforcement officers to first responders to EMS professionals to emergency department-based medical professionals—that first and foremost, we make sure we’re addressing these individuals as patients and prioritizing their medical care.”

The term “excited delirium” first appeared in two medical papers on the effects of cocaine intoxication by Charles Wetli and David Fishbain in 1981 and 1985. Wetli, was Miami’s deputy chief medical examiner, later applied his theories to the deaths of 14 black women in Miami between 1986 and 1988.

In an interview with the Miami News, Wetli attributed the deaths to excited delirium, saying he believed Black people were particularly susceptible: “For some reason, the male of the species becomes psychotic, and the female of the species dies in relation to sex.”

It was later determined that the 14 women had been murdered by a serial killer.

Joanna Naples-Mitchell, an attorney and researcher with Physicians for Human Rights, says racist notions like to Wetli’s have pervaded the literature describing excited delirium, including the 2009 ACEP paper. “That paper really laid out the criteria for identifying the signs and symptoms of excited delirium,” Naples-Mitchell says. “And some were overtly racist, including noting that someone might be possessed with superhuman strength or be impervious to pain—which are racist stereotypes about Black people that have led to all sorts of medical racism in this country for decades.”

Excited delirium became more prevalent in medical examiner reports after the 2005 publication of a book on the topic by Theresa Di Maio and Vincent Di Maio, which claimed that many deaths in police custody were wrongly attributed to positional asphyxia rather than excited delirium.

According to Naples-Mitchell’s research, the TASER corporation (the manufacturer of nonlethal taser weapons) bought and distributed at least a thousand copies of the Di Maios’ book and distributed them to medical examiners across the country.

Naples-Mitchell says TASER was closely allied to the movement to recognize excited delirium. She noted that a 2021 study by Osagie Obasogie in the Virginia Law Review found that of 166 deaths attributed to excited delirium in police custody between 2010 and 2020, 46 percent involved Taser use.

Obasogie’s study also found that 43.3 percent of people whose in-custody deaths were attributed to excited delirium were Black and 56 percent were either Black or Latino. Mitchell notes that as video of encounters with law enforcement become more common—as in the case of George Floyd or Alexander Rios, an inmate in Ohio who died in 2019 after being held down by corrections officers—it becomes harder to attribute a death to excited delirium.

“Excited delirium has been a placeholder for real diagnosis for decades,” Roger Mitchell says. “And now that we have third-party objective video, the medicine has an opportunity to evolve.”

Though Gill claims that deaths from excited delirium sometimes happen outside of contact with law enforcement—he remembers filing one report involving a man who had an episode after taking PCP who died in his home—most these deaths take place in custody. A 2020 paper in Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology found that 90% of excited delirium deaths involved some form of restraint.

Daniel Wohlgelernter, a cardiologist who testified in the trial of the Tacoma police officers, says he’s confident that Ellis died of cardiopulmonary arrest triggered by restraint-related asphyxia—not excited delirium, as the defense contended.

“There was little to no probability that Ellis would have died in the absence of the prone restraint actions by the law enforcement officers,” Wohlgelernter says. This is contrary to claims made by the defense, including reference to a 1997 paper by Theodore Chan and Gary Vilke, which found that in simulated situations, restraint did not significantly affect respiratory function. Wohlgelernter says those studies neglected to consider the stress of encounters with law enforcement.

“If instead, I had you run up 20 flights of stairs in a commercial office building and then put you in a prone position with five people sitting on your back,” Wohlgelernter says, “you’re gonna run out of oxygen pretty darn quickly.”

Decades of substituting excited delirium for other causes has served to shift blame away from law enforcement, says California Assemblyman Mike Gipson, who introduced the bill banning excited delirium as a cause of death.

“I think one can draw the conclusion that this was to cover up people dying at the hands of law enforcement,” Gipson says. He noted that Colorado legislators interested in passing a similar bill recently reached out to him about details. In December, Colorado’s Peace Officers Standards and Training board struck all references to excited delirium from its training materials.

In February, the ABA House of Delegates recommended that all deaths in police custody be accounted for and receive proper scrutiny. It passed a resolution urging state and local governments to follow the federal Death in Custody Reporting Act and ensure there are independent investigations into all deaths in police custody and at correctional institutions. The resolution also recommends a check box on all US standard death certificates specifying whether a death is in custody.

When Elijah McClain was confronted by police in Aurora, Colorado in 2019, paramedics diagnosed the young Black man with excited delirium. After being beaten and put in a chokehold by police, McClain was injected with the sedative ketamine by paramedics, went into cardiac arrest, and died four days later.

“It was the protocols on excited delirium,” says Naples-Mitchell, “that led to the administration of ketamine, which seems to have caused his death, in addition to the excessive force used by officers when he was stopped while walking home, totally healthy.”

In December, two paramedics who administered ketamine to McClain were found guilty of criminally negligent homicide. When asked by the ABA Journal whether ACEP was considering revising a policy that recommends administering ketamine to those experiencing hyperactive delirium, Goodloe said, “The evidence-based recommendations in the 2021 paper specifically address prudent dosing of ketamine. The outlined dosing regimen is notably different than paramedics were reported to have administered in the encounter involving Mr. McClain.”

Many local jurisdictions still have emergency service procedures that mention excited delirium and advise responding with ketamine. Joe Meinecke, a spokesperson for the Tacoma Fire Department, which employs the paramedic who testified in the trial of the officers involved in Ellis’ death, said that its first responders follow county protocols—which currently advise responders to work with law enforcement officers to restrain people experiencing excited delirium and to sedate them with a 4mg/kg dose of ketamine.

Mitchell hopes other states will follow California’s lead in banning excited delirium.

“We should get rid of excited delirium because it’s not an accurate diagnosis of what has caused death,” Mitchell says. “It’s a description of circumstances.”

Gipson says his bill has brought the Quinto family some consolation. “They’ve said to me that these policies can’t bring Angelo Quinto back but can hopefully make sure that no one will have to go through what their family did and what Angelo experienced.”