Please Plea Me: Court Expands Effective Assistance of Counsel

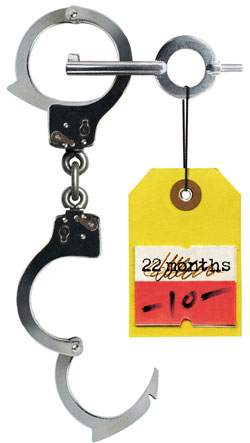

Illustration by Viktor Koen

The headlines seem like they were ripped out of the era of Chief Justice Earl Warren.

“Supreme Court decision expands defendants’ rights,” said the Washington Post. “Justices expand right of accused,” said the New York Times.

Of course, these weren’t from the Warren court’s pro-defendant heyday but from the current term under Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. In two 5-4 decisions in March, the justices ruled that criminal defendants are entitled to the effective assistance of counsel during plea bargaining.

The reality is that “criminal justice today is for the most part a system of pleas, not a system of trials,” Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote for the majority in Lafler v. Cooper. “If a plea bargain has been offered, a defendant has the right to effective assistance of counsel in considering whether to accept it.”

Lafler and an important companion case, Missouri v. Frye, were among a handful of rulings this term in which the court addressed constitutional issues surrounding effective counsel. In each case, the justices ruled in principle for the criminal defendant’s side, even if it denied relief to a particular defendant in one case.

“The court is trying to make access to counsel meaningful in a range of settings,” says University of Pennsylvania Law School professor Stephanos Bibas.

ENDEMIC ‘HORSE TRADING’

In the plea-bargaining cases, Justice Kennedy noted in his March 21 opinion in Frye that in the modern criminal justice system, “horse trading” between prosecutors and defense counsel to a large extent “determines who goes to jail and for how long.”

He noted that 97 percent of federal convictions and 94 percent of state convictions are the result of guilty pleas. Quoting a law review article, he added that plea bargaining “is not some adjunct to the criminal justice system—it is the criminal justice system.”

The Missouri case involved Galin E. Frye, who in 2007 was charged with driving with a revoked license, for which he faced four years in prison as a felony. He had three prior convictions for the same offense.

A prosecutor sent a letter to Frye’s lawyer offering a choice of two plea bargains. One involved a three-year sentence on paper, but with likely probation and a recommendation of only 10 days in jail as “shock time.” The second offer was to reduce the charge to a misdemeanor, with a likely 90-day jail sentence.

Frye’s lawyer did not tell him about the offers, and they expired before Frye faced a preliminary hearing. In the meantime, he racked up another arrest for driving with a revoked license. Frye pleaded guilty to the felony charge stemming from the 2007 arrest, and a judge sentenced him to three years in prison.

A Missouri appeals court ruled that Frye met both of the requirements for showing a Sixth Amendment violation of the kind that the Supreme Court outlined in the 1984 case of Strickland v. Washington: A criminal defendant must show that counsel’s performance fell below an objective standard of reasonableness; and, if counsel had performed adequately, the result of the proceeding —the trial, the sentencing hearing, the appeal—would probably have been different.

The appeals court said that Frye’s lawyer was deficient in not communicating the plea offers to him, and that the deficient performance caused prejudice to Frye because of the stiffer sentence he ended up with.

Lafler involved Anthony Cooper, a Michigan man convicted in a 2003 shooting incident. Cooper had fired a gun at a woman, hitting her in the buttock, hip and abdomen. She survived, but Cooper was charged with intent to murder, among other charges. He rejected a plea bargain offering a lesser sentence because his lawyer convinced him, incorrectly, that the prosecution would be unable to prove his intent to murder because the victim had been shot below the waist.

Cooper was convicted on all charges and sentenced to a mandatory minimum of 15 to 30 years. In a habeas proceeding, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Cincinnati held that Cooper’s lawyer had provided deficient performance by informing him of “an incorrect legal rule,” and that Cooper had been prejudiced by the ineffective assistance because he lost out on an opportunity for a lighter sentence.

DUTY TO CONVEY

In Frye, Justice Kennedy stopped short of defining “detailed standards” for the duties of defense lawyers in the plea-bargaining process. But “as a general rule, defense counsel has the duty to communicate formal offers from the prosecution to accept a plea on terms and conditions that may be favorable to the accused.”

Kennedy cited the American Bar Association’s Standards for Criminal Justice as one “important guide” for a lawyer’s performance in this area. The ABA recommends that defense counsel “promptly communicate and explain to the defendant all plea offers made by the prosecuting attorney.”

“No question about it, this is a big win,” says Margaret Colgate Love, a Washington, D.C., lawyer, who co-wrote the ABA’s amicus brief in the plea-bargain cases. Lafler and Frye follow in the footsteps of the court’s 2010 decision in Padilla v. Kentucky, which said defense counsel must advise defendants accepting a plea bargain about potential collateral consequences in civil matters, such as deportation.

“What is encouraging about these decisions is that they confirm, after the Padilla case, that the Supreme Court is genuinely interested in regulating the plea process,” Love says.

In weighing a remedy in the Missouri case, Kennedy said a defendant in Frye’s position must show not only a reasonable probability that he would have accepted the lapsed plea offer, but also a reasonable probability that the prosecution would have adhered to the agreement and that the trial court would accept it.

Because of Frye’s further arrest for the same offense in the meantime, Kennedy suggested it was doubtful the prosecution and trial court would have allowed the original plea offer to become final. The high court remanded Frye to the Missouri courts.

In Lafler, Kennedy rejected the state’s argument that a fair trial “wipes clean” any deficient performance by a defense lawyer during plea bargaining. He said the proper remedy in such cases could include requiring the prosecution to re-offer the original plea proposal, or for the trial court to weigh whether to give the sentence originally offered, the sentence the defendant received at trial, “or some thing in between.”

“The boundaries of proper discretion need not be defined here,” Justice Kennedy said. In Lafler, the high court set aside a trial court order of specific performance of the original plea and instead said the state should re-offer the plea. That would give the state trial court some discretion on how to proceed.

Kennedy’s opinions in both cases were joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen G. Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

FRACTURED DISSENTS

Justice Antonin Scalia delivered the main dissents in both cases. Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr. joined his Frye dissent, but only Thomas joined the Lafler dissent in full. (Roberts joined in part, and Alito authored a separate dissent in that case.)

“Until today, no one has thought that there is a constitutional right to a plea bargain,” Scalia said. “The court today embraces the sporting-chance theory of criminal law, in which the state functions like a conscientious casino operator, giving each player a fair chance to beat the house—that is, to serve less time than the law says he deserves. And when a player is excluded from the tables, his constitutional rights have been violated.”

The majority left much to be “worked out” in further litigation, “which you can be sure there will be plenty of,” Scalia said.

Kent S. Scheidegger—legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation in Sacramento, Calif., which filed an amicus brief in support of prosecutors in the two cases—calls the decision “stunning.”

The resulting harm to prosecution interests may only be “a leak instead of a flood, but leaks cause damage, too,” Scheidegger says.

Another advocate on the prosecution side had a more practical reaction. Dean A. Mazzone, the chief of the enterprise and major crimes division of the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office, notes that for about seven years his state’s court system has recognized that the Sixth Amendment is implicated in plea bargaining, and “the sky didn’t fall.”

The Supreme Court decisions “will require much more formality in the plea-bargaining process,” Mazzone says. There will no doubt be questions about what constitutes a formal plea offer, and there will probably be movement to put everything in writing, he says. And the court was not altogether clear on what the remedy will be in cases where ineffective assistance is provided, he says.

Bibas, a former clerk to Kennedy, wrote a law review article about plea bargaining that Kennedy cited in Lafler. The article, from the California Law Review, is full of vivid analogies, including one cited by Kennedy that a post-trial sentence, imposed in only a small proportion of cases, is a bit like “the sticker price for cars: Only an ignorant, ill-advised consumer would view full price as the norm and anything less a bargain.”

And in an argument for greater state procedural protections for plea bargaining, Bibas wrote: “It is astonishing that a $100 credit card purchase of a microwave oven is regulated more carefully than a guilty plea that results in years of imprisonment.”

Bibas agrees that the plea-bargaining decisions were significant.

“First with Padilla, and now with Frye and Lafler, the court is turning to this huge area it has traditionally left alone,” he says. “I think [the rulings] will lead a process that all in all has had very low visibility into at least the twilight, if not the sunlight.”