Cure or Con? Health products touted on social media are slipping by regulators

Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

Talk show host Dr. Phil McGraw held a jar of green liquid in his hands. He carefully opened the lid, sniffed the contents and winced. Next to him, the creator of “Jilly Juice” excitedly told him she believed her concoction of fermented cabbage juice purged the gut of parasites and allowed the body to begin absorbing nutrients again.

Jillian Mai Thi Epperly recommended drinking up to a gallon of the juice each day, which followers mixed and fermented at home. If they needed guidance, she charged consulting fees of $70 per hour.

Epperly told McGraw that her juice sparked a healing process so profound that it could regrow organs or limbs, enable people to live to 400 and cure cancer. She also claimed her juice could “reverse” AIDS, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Down syndrome, homosexuality and Type 2 diabetes.

“I assume you have pictures of people who have regrown arms and stuff?” McGraw said.

“Jilly Juice” creator Jillian Mai Thi Epperly got a warning letter from the Federal Trade Commission in 2018 over her claims that her fermented cabbage juice protocol could cure diseases. Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

Epperly said she did not because she had “only been doing this for a year,” and admitted her “training” came from the internet.

Since launching her protocol, Epperly primarily shared her claims through social media, including YouTube videos, allowing her to avoid legal scrutiny because regulators simply can’t keep up with the volume of such products promoted online.

After McGraw called Epperly’s claims “outrageous and offensive,” she returned home to Canton, Ohio, and continued her social media postings. Then, in May 2018, the Ohio Attorney General’s Office, which had become aware of Epperly’s protocol, issued a letter and demanded she substantiate her claims. Five months later, the Federal Trade Commission took its first steps by sending her a warning regarding claims on her website.

Questionable claims

Epperly is among a handful of self-described healers who have been told to stop advertising unsubstantiated health claims on social media. From diet shake powders to vitamin supplements, social media is filled with posts and targeted ads for health products and services. While some products, such as vitamin supplements, are benignly ineffective, others make outrageous claims that attract desperate consumers hoping to cure cancer, HIV and other diseases.

Social media offers cheap and targeted advertising that regulators don’t have the time or resources to fully monitor. Deceptive health claims that would land a company in court if made on television or radio are slipping by online. State and federal regulators as well as watchdog groups say the problem is only growing, allowing many to escape legal accountability for selling or promoting products that don’t live up to their promises.

“Millions of people are on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook or may have blogs,” says Mary Engle, an attorney with the FTC’s division of advertising practices.

“We cannot monitor all those. We have limited resources. We want to focus our attention on the most potential for injury. We look at how widely disseminated the claims are and if you can actually purchase the product.”

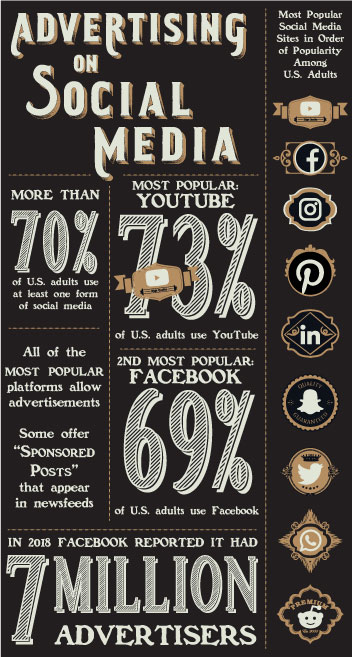

YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, LinkedIn, Snapchat, Twitter, WhatsApp and Reddit—according to the Pew Research Center—are the most popular social media sites by order of popularity among U.S. adults in 2019. More than 70% of U.S. adults use at least one form of social media. YouTube is the most popular, with 73% of U.S. adults using the site. Facebook is the second-most popular at 69%.

All of these platforms allow advertisements. Some businesses pay for “sponsored posts” that appear in a newsfeed. In the last quarter of 2018, Facebook reported it had more than 7 million advertisers. Other businesses create a free “business page” in which they can promote products and services to followers. Facebook has more than 80 million business pages.

Social media is a place where advertisements and business pages go relatively unchecked. A supplement company might claim its vitamins cure cancer; an uncertified health coach might promote her services. Unless complaints flood regulators’ offices, most promotions remain unchallenged.

“There are thousands of fly-by-night companies. They are selling the same products, so they are competing to make the most outrageous claims,” says Matt Simon, associate litigation director at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, an advocacy group based in Washington, D.C.

Consumer advocacy groups, such as CSPI or Truth in Advertising (TINA.org), expose deceptive advertisements online, but regulators typically do not have the time or means to respond. There’s too much content for agencies such as the FTC to monitor. Facebook reported an average of 1.62 billion daily active users for September 2019.

Regulators are inundated with complaints. “Just to be clear, we get hundreds of thousands of complaints a year. We can’t follow up on all of them,” Engle says.

When the FTC takes action, it typically sends warning letters to allow companies to remove posts or change their website content, Engle says. In extreme cases, the FTC sues the company and collects damages on behalf of injured parties. Civil cases, whether settled or tried in court, typically come with stipulations for the defendant. Companies or individuals might be barred from making future statements or advertising in a specific medium. If the stipulations are ignored, the judge can hold the defendant in contempt.

Kevin Trudeau is serving a 10-year prison sentence for contempt of court after he violated a court order by promoting this book. Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

The FTC first sued TV pitchman Kevin Trudeau in 1998, charging him with making false and misleading claims in infomercials. A subsequent 2004 federal court order barred Trudeau from making false claims about products. Trudeau was later found to have defied that order by misrepresenting the contents of his 2007 book The Weight Loss Cure ‘They’ Don’t Want You to Know About. The book, prosecutors argued, was a dangerous diet plan that required weeks of near-starvation. Although the book was protected under the First Amendment, Trudeau’s late-night infomercials were not protected speech. For violating the order, Trudeau was ordered in 2009 to pay more than $37 million, and in 2014 he was sentenced to 10 years in prison for criminal contempt.

But such actions are rare, and that means most companies can make egregious claims without facing resistance.

TINA.org has more than 3,000 examples of inappropriate health claims made on social media, says Bonnie Patten, an attorney and the group’s executive director.

Patten says many people are unaware of the law on deceptive advertising. Advertisements that claim a product treats, cures or minimizes symptoms of a disease or medical condition are technically promoting a drug. Disease-treatment claims must be backed by reliable scientific data and approved by the FDA, Patten says. “If you look at a disease-treatment claim, you will need at least one peer-reviewed, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a large sample size of humans to make such a claim.”

Not just for better sleep

MyPillow, for example, is a Minnesota-based company that uses infomercials and social media to sell a line of pillows. In 2016, TINA.org pushed district attorneys in California to take action against the company’s advertising practices. The company posted testimonials on YouTube, Facebook and Twitter from customers who claimed the supportive pillow helped with sleep apnea, a condition that causes difficulty breathing during sleep. According to the complaint, testimonials also included statements such as: “MyPillow can help your fibromyalgia; MyPillow can help your snoring; MyPillow can help your TMJ; MyPillow can help your migraines and headaches.”

MyPillow paid nearly $1 million in civil penalties in 2016 to settle deceptive advertising complaints. The company has since stopped using testimonials in social media making claims like the ones in this illustration. Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock.

MyPillow agreed to settle the case in 2016. The company paid $995,000 in civil penalties and made a $100,000 donation to a homeless shelter. The company also agreed to stop using disease-treatment claims in advertising.

The use of testimonials can be a legal gray area. A customer is free to post an opinion about a product and make a claim that could be exaggerated or untrue. Patten says the problem is that many businesses don’t realize that testimonials cannot make disease-treatment claims, according to FTC regulations. And such claims shouldn’t be repeated in social media updates or sponsored advertisements.

In 2019, TINA.org publicly criticized Your Super for posting testimonials from customers saying the supplements could cure irritable bowel syndrome and other conditions. The company has since removed such testimonials from its website. Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock.

Your Super is a California-based company that sells powdered supplements that can be sprinkled over food or into shakes. According to a 2019 alert posted by TINA.org, the company used a Facebook advertisement to claim the mixes cured eczema for one of the founders. The company also used Facebook reviews in which customer testimonials claimed the product helped cure conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome and even served as an alternative to chemotherapy.

TINA.org publicly criticized Your Super, saying that if it uses customer endorsements in its marketing materials, it must comply with the law. “And claims to treat, cure, alleviate the symptoms of, or prevent developing disease are simply not permitted by law without FDA approval,” the alert stated.

Neither of the two founders of Your Super responded to an interview request from the ABA Journal. The founders did alter part of their website to exclude testimonials in which “happy customers” made disease-treatment claims. However, the company continued to use targeted, sponsored posts on Instagram, including a June 9, 2019, post that quoted a testimonial in which a customer with hypothyroidism and polycystic ovary syndrome claimed she “really believed” the product was responsible for her improved health.

A question of free speech

Small business owners who run their own advertising campaigns through social media might lack the legal savvy to know when they’ve crossed the line. And there can be confusion as to what qualifies as personal, professional or commercial speech, and how free speech protections vary for each speech type. Personal speech is protected under the First Amendment, but commercial speech is subject to regulation—even if it occurs in a social media status update from a personal account.

Infographic by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

Engle says the FTC is “platform neutral,” which means it considers all social media platforms to be places where speech might occur. Even a personal social media account can be subject to scrutiny for commercial speech if it’s placed within a promotional context. “The key is what is the person’s economic motivation in that post to sell the product or service,” she says.

In general, commercial speech must meet two standards, says Rodney A. Smolla, dean and professor at Widener University Delaware Law School. First, the promoted product or service must be legal. “There is no First Amendment right to advertise the sale of heroin,” he says. “Second, the advertising must not be misleading. If you make claims for a product or service that are not true, then you do not have any First Amendment protection. You have no right to say this milkshake will cure cancer if it’s false. It’s permissible for the government to say you can’t make that claim.”

Professional speech is content-driven. How the message is delivered determines whether it is subject to regulation. Smolla says medical care professionals can give broad advice to the general public in books, speeches or social media updates. Unlicensed individuals are also free to give their general opinion within these contexts.

Smolla says professional speech becomes regulated when it is specific advice given in exchange for a fee. The law also regulates who has the credentials required to give such advice. In Florida, for example, the state licenses registered dietitians. Unlicensed individuals who call themselves “consultants” or “coaches” can offer broad, general advice in a public forum. But they cannot offer specific nutrition advice in exchange for a fee. “The courts would say you are practicing medicine without a license,” Smolla says.

Health coaching controversy

A Florida woman faced that very allegation. Last year, a U.S. District Court determined that Heather Del Castillo of Fort Walton Beach was practicing dietetics without a license. Del Castillo had called herself a “health coach” and charged for personalized nutrition advice. She had no degrees in nutrition or health sciences. She also did not have the mandatory clinical hours required for a state license.

Del Castillo began her coaching business in 2015 in California, where state regulations allow unlicensed individuals to seek payment for specialized diet advice. According to her LinkedIn profile, she graduated in 2004 from California State University at Long Beach with a bachelor’s degree in geography, recreation, travel and tourism.

Before setting up her coaching business, Del Castillo completed an online certificate in holistic health coaching from the Institute for Integrative Nutrition, an unaccredited school based in New York City. She began soliciting business in local magazine advertisements as well as social media accounts. In 2017, Del Castillo and her husband relocated to Florida and continued promoting her services.

On social media, “Heather Health Coach” described herself as a “certified” health coach. She used Facebook to advertise her personalized nutrition coaching. A six-month individualized plan included 13 sessions with the first one for free and the remaining 12 costing $95 each. Del Castillo met with clients in person and via phone, Skype and Google Hangouts.

By 2017, Del Castillo had “about a dozen clients in Florida and several outside the state,” according to one of her attorneys, Ari Bargil with the Miami office of the Institute for Justice, a libertarian public interest firm.

A Florida dietitian took notice of Del Castillo’s promotions and complained to the Florida Department of Health. An investigator posed as a potential client and emailed Del Castillo. She responded with a description of her services and attached a personalized health history form for the prospective client to complete. In May 2017, the department determined that Del Castillo was practicing without a dietitian’s license and sent her a cease-and-desist letter. Del Castillo was fined $500 as well as $254.09 in investigative fees.

In response, Del Castillo sued the department. She claimed that giving diet advice was free speech, and that Florida’s Dietetics and Nutrition Practice Act, which requires dietitians to be licensed, violated her First Amendment rights. In a response to the department’s motion for summary judgment, Del Castillo’s attorneys argued “… that making it a crime to advise adults on what to buy at the grocery store is a restriction on speech that should be subject to First Amendment scrutiny.”

Several women named Heather are using a variation of “Health Coach Heather” or “Heather Health Coach” to sell personalized wellness advice. Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock.

But in July 2019, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Florida in Pensacola agreed with the Florida Department of Health. Del Castillo could not charge for individualized nutrition counseling services. Del Castillo’s attorneys filed an appeal. Bargil says he takes issue with how Florida regulates only a specific type of professional speech. A special license is not required to give exercise or cooking advice in exchange for compensation, but it is required for diet advice, Bargil argues.”The First Amendment protects the basic exchange of ideas, and this is just such an instance,” he says.

Del Castillo continues to work as a health coach (but does not give one-on-one diet advice for a fee) while the case is on appeal. Her website offers classes in essential oils as well as a “personalized health coaching” program for $195 that she says will “radically improve your health and happiness.”

A crowded marketplace

Del Castillo has steep competition in the health and happiness market. In fact, she is one of several unlicensed women named Heather who use a variation of “Health Coach Heather” or “Heather Health Coach” to sell personalized wellness advice.

One is from Phoenix, another from Canada, a fourth from South Carolina and a fifth from Boston. A sixth “Heather Health Coach” lives in Iowa and describes herself as a “BioEnergetic Practitioner.” The others also have online certificates from the Institute for Integrative Nutrition.

The IIN’s online program costs $6,000 for 40 weeks and can take as little as five hours a week to complete. Only a GED or high school diploma is required for admission, and more than 100,000 people have earned certificates from the school, according to the IIN’s website. The low barrier to entry, in terms of cost and qualifications, means competition can be tough for health coaches trying to sell their services.

Matt Simon, the attorney with the CSPI, says competition for products that are difficult to distinguish can inspire more exaggerated claims. The greatest risks to consumers, he says, are not coming from mainstream products advertised during prime-time television or sold on drugstore shelves. “The further you get away from mass media advertising, the worse the claims become,” Simon says. “It all exists out there on the internet. The social media landscape makes it much easier for these companies that are not going to put their product on CVS shelves to market to desperate consumers looking for a cure.”

The social media landscape, however, seems to be a training ground for some companies to test unsubstantiated claims. Some companies take these claims to traditional advertising mediums after YouTube clips or Instagram posts attract customers but not regulators. In some instances, the traditional ads catch attorneys’ attention, especially when the products can cause harm.

In 2018, the FTC sued Nobetes for making unsubstantiated claims that its product could reduce high blood sugar. The company settled with the FTC and sent more than $60,000 in refund checks to consumers last year. Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

In 2018, the FTC sued Nobetes, a supplement company that used advertisements on YouTube, Facebook, television and radio to promote its product as a way to reduce high blood sugar levels. According to the complaint, consumers could face injury if they took Nobetes, a product that was not scientifically proven to manage diabetes.

The complaint includes transcripts for Nobetes’ videos on YouTube. One video began by asking viewers if their blood sugar levels were dangerously out of control. Then, an actor standing in front of two framed diplomas described how each pill had “35 supplements” that fill the “nutrient shortages that diabetes causes.”

The company settled with the FTC, and more than $60,000 in refund checks were mailed to consumers in August 2019. At least one of the advertisements, however, was still available to view on YouTube in December.

Long history of quackery

While promoting products on social media is relatively new, snake oil salesmen and quacks have been targeting consumers for centuries. Before the FDA regulated drugs, corner stores sold their own proprietary blends of supplements and cure-alls, says Lydia Kang, an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and co-author of Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything.

“Social media is an amped up version of what was happening at the turn of the century,” Kang says.

Kang defines a quack as someone who tries to profit from selling a product they know doesn’t work as promised. “It’s a fuzzy area because there are people who believe their treatments work, but there is poor or no evidence to support their claims,” Kang says.

Smolla says regulatory agencies have to focus on the companies that have the potential to cause the most harm.

“It’s buyer beware these days. There’s little the government can do to keep up. The choice is to go after the most egregious cases,” Smolla says.

While regulatory agencies go after the most egregious cases, consumer organizations such as the CSPI are calling for more funding and support for agencies such as the FTC and FDA.

“The FDA has about 25 employees in its office for supplements to police 80,000 supplement companies,” Simon says. “That’s woefully inadequate.”

With such little staffing, the FDA relies on complaints from organizations such as TINA.org or the public to learn about self-proclaimed healers like Epperly who used social media to pitch her Jilly Juice protocol.

Regulators, however, didn’t take action until after she appeared on national television. Epperly did not respond to an ABA Journal interview request.

She continues to post daily to Facebook, where she has more than 6,000 followers, as well as to YouTube, where she has more than 1,700 followers. On YouTube, she posts videos almost daily—many as long as an hour—in which she sits in her swivel chair and discusses her “revelations,” such as there are spirits that live within the body.

Because Epperly isn’t giving individualized advice in her videos or social media postings, she is legally permitted to share her broad, unspecified advice to anyone willing to listen.

This article ran in the February-March 2020 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline:”Cure or Con? Self-described healers and health coaches avoid regulatory scrutiny by promoting products on social media”

Emilie Le Beau Lucchesi is the author of Ugly Prey and This is Really War. She holds a PhD in communication from the University of Illinois-Chicago and studies health communication, medical history and stigma communication.