Breyer: Nat'l Legal Systems Are Finding Common Ground

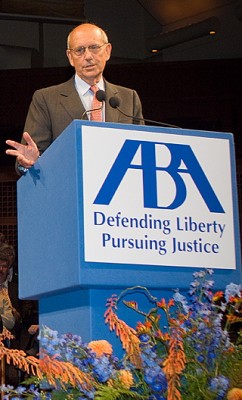

Justice Stephen Breyer.

By Patrik Agrast.

Updated: The laws of the United States and other nations are increasingly becoming pieces of a larger fabric as they seek to address issues of common interest, said U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer this afternoon in a speech at the 2007 ABA Annual Meeting in San Francisco.

“Law is seeing itself as facing a set of common issues,” said Breyer, who addressed the ABA Rule of Law Initiative Luncheon. And increasingly, legal systems are addressing those issues in a more universal way rather than approaching them as matters that should be addressed separately by the domestic legal systems of each nation. (Video of Breyer from ABA Media Relations)

While Breyer did not discuss this trend in the context of any particular case on the Supreme Court’s docket, he said it is becoming increasingly important for U.S. lawyers and judges to understand how various legal issues are dealt with by other legal systems. He cited the growing body of European Union law and differing approaches to defining sovereign immunity as examples, but added that issues such as antitrust, tort law and commercial piracy are some of the other areas where the trend is occurring.

A growing body of law also is the byproduct of such agencies as the World Trade Organization and treaties like the North America Free Trade Agreement and, perhaps soon, the international Law of the Sea Treaty, which recently has been advancing toward possible approval by Congress.

“That’s the world, and we know perfectly well that’s the world,” Breyer said. “And we have to know something about it.” Breyer stopped just short of adding, “ … but we don’t.” Instead, he said, “And we’re getting those answers in briefs from lawyers in France and Germany and elsewhere.”

Breyer recalled attending a conference commemorating the creation of the civil code, which is the basis for domestic law in most European countries and other regions of the world. As speakers discussed how the civil code has changed, Breyer said, “I asked myself, ‘Where am I? I could have been in San Francisco, St. Louis or Chicago. The issues were the same.”

For lawyers, the key is to communicate across the lines of national legal systems, said Breyer, who received this year’s Rule of Law Award from the ABA.

Taking a gentle poke at the ABA, “with its 400,000 members and 800,000 committees,” Breyer said that, ultimately, all the meetings that lawyers seem to love so much bring progress, even if it is in fits and starts. “You talk, and you listen, and ideas develop,” he said.

Breyer gave his speech amid growing activity by the ABA on the international front. The luncheon, which was first held more than a decade ago to recognize the work of what was then known as the Central and East European Law Initiative, now is sponsored by the Rule of Law Initiative, which oversees the work of ABA initiatives in Europe and Eurasia, Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East and North Africa.

And the ABA’s World Justice Project will mark its official launch at the end of the annual meeting, when William H. Neukom of Seattle begins his one-year term as the association’s president. The project—Neukom’s chief presidential initiative—will seek to identify and measure how the rule of law can be a tool for creating greater economic opportunity and social equity in countries throughout the world.

About four hours later, Justice Breyer was back at the podium, giving the keynote address to the opening assembly of the annual meeting. In those remarks, he said that judicial independence can only exist to the extent that it is supported by popular opinion.

“The very point of being a judge is to be independent,” Breyer said. “But you need public support to have an independent institution.”

Perhaps inevitably in speaking to an audience made up primarily of lawyers, Breyer cited some historic Supreme Court cases to illustrate the principle of judicial independence. But he also described it in the simplest of terms. At its most fundamental, “judicial independence is when the least popular person in the community gets the same treatment in court as the most popular.”

The merits of judicial independence is clear to the justices of the Supreme Court, the rest of the judiciary and the legal profession, said Breyer, who make up some 1.2 million people in the United States. But, he said, “I’m not positive how much it means to the other 299 million of us. This system—and basically it is a good system—floats on a sea of public opinion.”

The most important aspect of controversial decisions issued by the courts, said Breyer, is not necessarily their outcomes, “but that people accept them. Not judges or lawyers, but the other 299 million of us.” Originally posted at 7:10 p.m. CDT.