Law and politics comingle in DC insider’s memoir

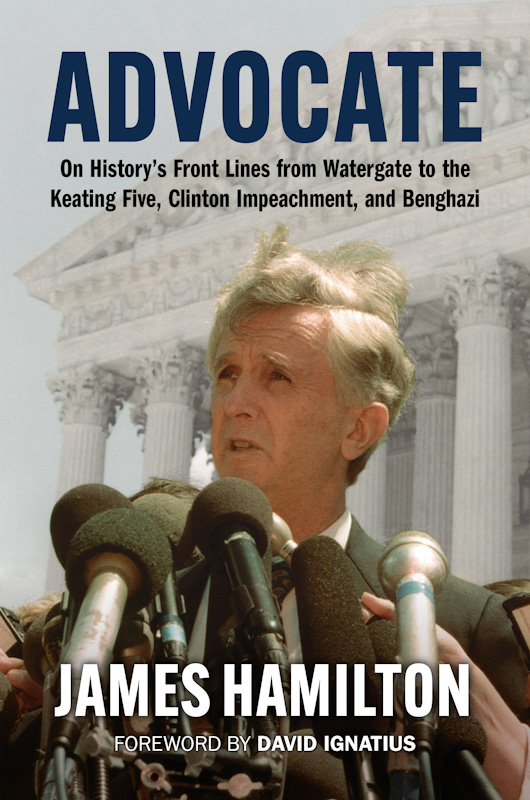

After decades as a legal insider and observer of some of the most consequential moments in modern U.S. history, James Hamilton retired from law and picked up his pen. In his new memoir, Advocate, Hamilton shares fascinating tales of the power brokers and politicians who helped steer the course of the country.

From his participation in high-profile congressional investigations to his experience vetting vice presidential, cabinet and Supreme Court candidates, Hamilton shares personal details and insights that will engage history buffs as well as lawyers. Advocate delves into Hamilton’s involvement with investigations including Watergate, the John F. Kennedy assassination, “Debategate,” the Keating Five, the Clinton impeachment, Vince Foster’s suicide, the Valerie Plame affair and the Major League Baseball steroids scandal—among others.

Hamilton’s expansive career offers a glimpse behind the scenes into Washington political intrigue, and an intimate view of some of the most sensational and controversial events of the past 50 years. A uniquely American tale of the comingling of law and politics, Advocate fills in the gaps of historical events but also offers some lessons learned.

Q. You’ve been involved in some of the most interesting and seminal issues and cases in the past 50 years, from the investigation of John F. Kennedy’s assassination to the Benghazi tragedy. Of the high-profile incidents you’ve been involved in, which stands out most from a personal or emotional perspective?

A. That would be my experience as assistant chief counsel for the Senate Watergate Committee, which conducted the most riveting and successful congressional investigation in our history. The New York Times called the committee’s hearings in the spring and summer of 1973 “Appointment TV”; 60 million people watched John Dean testify about the “cancer” on the Nixon presidency. The hearings, which Bob Woodward has called the “gold standard,” were successful because Chair Sam Ervin, a Democrat, and Vice Chair Howard Baker, a Republican, wanted a fair, bipartisan investigation, because Chief Counsel Sam Dash knew how to tell a story and because we discovered the White House tapes that caused the downfall of a corrupt president. My personal role was to head the investigation into the Watergate break-in and cover-up, and thus I was in the thick of things.

Q. Having been involved in so many historic political investigations, what are your thoughts on how the process has evolved over time?

A. The Senate Watergate Committee investigation was tough, but fair, and was conducted in the old-fashioned way—by putting witnesses, often hostile, on the stand and subjecting them to cross-examination. Many more recent congressional investigations have not been fair—witness the disgraceful treatment by House Republicans of Admiral Mike Mullen, one of the most distinguished military leaders of our time, whose “offense” was writing, along with Ambassador Tom Pickering, an objective report on the Benghazi tragedy for Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. The House January 6 Committee deviated from the Watergate Committee cross-examination model and instead presented highly scripted, video-heavy hearings, which were quite effective.

Q. You are widely known for being the “dean of vetting” for candidates for the vice presidency, the Supreme Court and cabinet positions. How do you think the process has changed, or has it, and particularly I’m thinking of high court candidates?

A. The vetting process has become much more thorough, at least on the Democratic side, which the internet has made possible by allowing wide access to information. When I started vetting various candidates for the Clinton administration in 1992, I developed four criteria for that exercise—thoroughness, confidentiality, expedition and respect. The respect requirement is important because, even though you are asking candidates the most invasive questions about their professional and personal lives, you should treat people who have reached the pinnacle of American life with respect. As to the high court, particular emphasis is now placed on age and health, as well as judicial philosophy, because you want justices who share the president’s views on the court for a long time.

Q. Following up on that, you argued against Brett Kavanaugh in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. What was that about and what stands out to you about that experience, and the fact that he is now a justice?

A. The case involved notes of my conversation with (Bill) Clinton’s Deputy White House Counsel Vince Foster nine days before his suicide and established that the attorney-client privilege survives the death of the client. Kavanaugh and his boss, Ken Starr, in unsuccessfully attempting to break the privilege, were overreaching and seeking a result that would have been disastrous for the profession and our clients, who often are hesitant in any circumstance to be candid with their attorneys. In my view, Starr and Kavanaugh were blinded by their desire to bring down the Clintons. One can hope that Justice Kavanaugh, a capable lawyer, is more objective and respectful of basic legal principles in his rulings on the court.

Q. You have seen how the sausage gets made: But as your book notes, a good D.C. lawyer needs to be prepared to represent “heroic public servants and dishonest scoundrels.” Looking back how did you balance walking that tightrope?

A. If you practice white collar law, some of your clients will not be paragons of virtue. If that is your main criterion, you often will be unemployed. Our job as lawyers is to help those who, by misdeed or mistake, have run afoul of the law. That said, on occasion I have refused to represent, or have fired, clients whose views or conduct I thought repugnant. I will say that I have found that most of my politician clients, even those who have committed grievous wrongs, have some admirable characteristics and certainly are entitled to diligent representation.

Q. The book is intended to be not just a recounting, but also a template for those interested in learning from your triumphs and mistakes. Why did you want to do this?

A. Several reasons. The book seeks to provide lessons from the various historical matters I have been involved in. Lessons flow both from successes and mistakes. I think that authors being candid about their shortcomings lends credence to their books. A number of my flubs are interrelated with good stories, and frankly, I cannot resist telling a good story.

Q. What is the advice you give to young lawyers interested in pursuing a legal career, and in particular, one where politics is involved?

A. The last chapter of the book lays out my advice to young lawyers. In addition to making enough money to provide your family a decent life, I have found it important to work with people you like and respect, sometimes difficult in the political arena in Washington; to work on matters that hold your interest; and, at least part of the time, to engage in activities that are worthwhile and fulfill your societal obligation as a lawyer. Achieving the latter two goals may result in reduced compensation, but joy and pride in your work is worth the lumps.