New PBS documentary shows how one man’s legacy changed the trajectory of American race relations

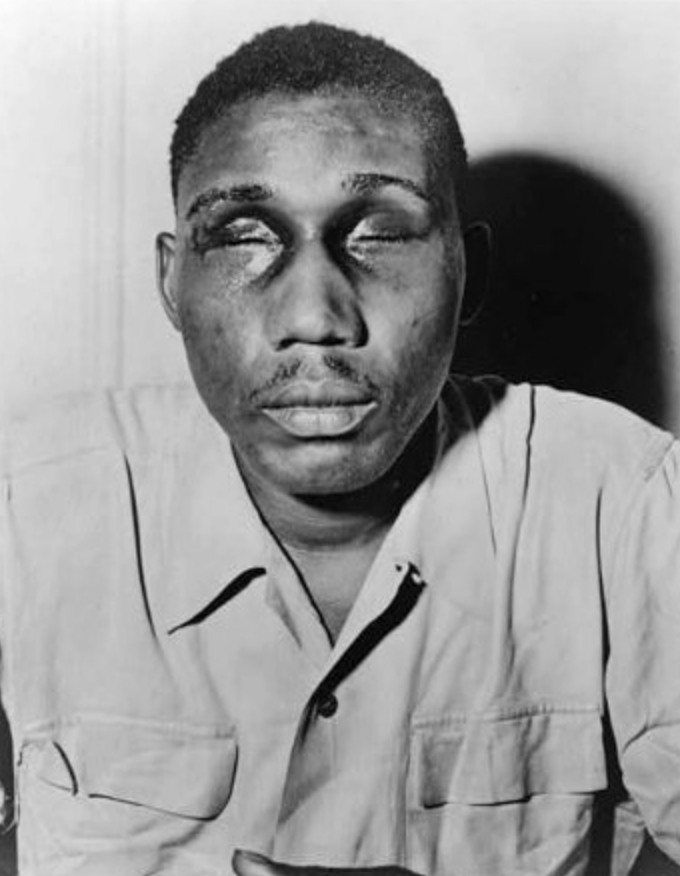

World War II veteran Isaac Woodard with his eyes swollen shut from aggravated assault and blinding. Woodard was assaulted Feb. 12, 1946. Photo by J. DeBisse via Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress.

Individuals and companies reach out to me regularly regarding their new law-related TV projects. Recently, I received an email regarding the new PBS documentary The Blinding of Isaac Woodard, which first aired March 30. I was sent a link to a press preview that gave access to the production prior to its release.

I was not very familiar with the subject’s name. I know PBS is a remarkable network with a wide range of educational material at its disposal, but I didn’t know the man behind the documentary’s title. Before deciding whether to devote myself to the program’s nearly two-hour runtime, I decided to do a little research.

A quick internet query for the documentary’s title initially brought up the Woody Guthrie tune by the same name. Seeing how Guthrie and I are both Oklahoma born and bred, yet I was still unfamiliar with the plight of Isaac Woodard, I decided I’d read the song’s lyrics and go from there.

A man on a bus

Guthrie’s song tells Woodard’s tale from the first-person perspective: He was an African American Army veteran who, directly after returning from World War II, was brutally beaten, blinded and arrested by white Southern law enforcement officers after receiving his discharge from the service—all while wearing his U.S. Army uniform with service-related awards, including a battle star from the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal.

The lyrics piqued my interest. I began viewing the documentary, and I’m glad I did. As is often the case with many of PBS’s products, substance is preferred over style. The presentation most likely won’t keep the attention of today’s frenetic viewing audience who constantly crave the cut scenes and in-court footage that is the hallmark of true crime’s most recent iterations.

Hopefully viewers will still be taken in by this documentary, as they would miss out on a very well-crafted broadcast otherwise, as the documentary will enthrall anyone familiar with the general style of PBS’s wares. The extensive use of historical imagery in the form of photographs and newspaper clippings gives the documentary a Ken Burns vibe that hits its desired mark more often than not.

The Blinding of Isaac Woodard begins right where the rubber hits the road, starting much akin to the Woody Guthrie synopsis cited above. Individuals fascinated by the true crime genre’s inner-workings (including its origins and present-day form) will be interested in learning how Woodard’s story gained an extreme level of national appeal relative to its day and age.

Orson Welles brings the national spotlight

I noted the documentary begins by introducing Woodard to the audience; however, that introduction is not merely left to the first-rate voiceover talent of the show’s narrator. No, the opening comes courtesy of an unmistakably timeless voice. Right out of the gate, the audience is treated to the tones of the one and only Orson Welles.

Without much background knowledge and fully aware Welles has been deceased for over 35 years, my ears perked as I realized this tale must be something momentous to garner not only a Woody Guthrie tune but also an Orson Welles rendition of Woodard’s affidavit. As the documentary continued, I grew to understand more about Welles’ involvement.

Once Woodard’s maiming was reported, the NAACP became involved. The prejudice and violence Woodard experienced was not isolated. In 1946, the NAACP had its hands full with cases involving racial discrimination and violence against Black servicemen returning home from the war.

The documentary does excellent work explaining the underlying reason: As these war heroes returned home in their uniforms, they inevitably struck fear in the ignorant minds of many Southerners. Racists relied on African Americans to “know their place” through fear of danger and death.

However, these Black servicemen had just faced both—and won. They returned from fighting a war against a fascist regime that had steamrolled through Europe on the back of a platform based on the notion that some races of men were less than others.

Surely, after defeating the enemy and the associated mindset, they could return home to a better place, right? Wrong.

Racial violence surged in 1946, and Woodard’s situation was sadly one of many. Nevertheless, the fact this man had been blinded by white officers of the law—while wearing his Army uniform and the emblems of his sacrifice—struck a distinct chord. The NAACP wanted to get as much publicity as possible for Woodard’s cause, so they reached out to Welles. Isaac Woodard’s assailant had not yet stepped forward, and the hope was to discover who had committed these crimes and in what jurisdiction.

At the time, Welles had a radio show broadcast nationally every week. Whether it was his hatred of racial inequality, or more so his love of a good “whodunnit,” Welles devoted five weeks to Woodard’s story, keeping his audience engaged by pressuring “Officer X” to show himself and own up to his deed.

Welles even went so far as hiring a private investigator to follow the bus route Woodard traveled after being honorably discharged to determine to which jurisdiction the officer belonged. He threatened that “Officer X” was going to be uncovered, and that’s precisely what happened.

The seeds of desegregation

Once the officer was identified, civil rights groups across the country began writing letters demanding prosecution of the now-known attacker. Those demands initially fell on deaf ears until NAACP Executive Secretary Walter White reached out to President Harry S. Truman, pleading for the Department of Justice to prosecute the man responsible for beating and maiming Woodard.

President Truman was initially hesitant. Yet, his background as a deployed WWI veteran himself, and the internalization that Woodard was treated so horribly while likewise returning home from a foreign war, led President Truman to direct the DOJ to move forward with charges.

Like so many cases of its kind, a jury ultimately acquitted the white officer. However, that acquittal turned the tide and opened the eyes of the federal district judge who presided over the trial. From that day onward, Judge Julius Waties Waring became an unexpected, major player in the civil rights movement of the 1940s and 1950s. Judge Waring began to take more cases on his docket dealing with racial injustice. One such case, Briggs v. Elliott, set in motion a meeting with the NAACP’s top attorney, Thurgood Marshall.

According to the PBS documentary, Judge Waring (in an ex parte communication) explained to Marshall that he did not want to try any more “equalization” cases; instead, he wanted Marshall to bring him a lawsuit to serve as a challenge to the constitutionality of segregation as a whole. He convinced Marshall to dismiss the original complaint in Briggs and refile the cause as a challenge to Plessy v. Ferguson’s doctrine of “separate but equal,” focusing on the “separate” aspect of public schooling.

Marshall initially lost Briggs. As the case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal, though, it was consolidated with four other cases, one being Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Those five cases allowed the Supreme Court to overrule Plessy and find segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

The result is a documentary that effectively explains the differing contributions so many people made to that final legal decision, and how the beginning can’t be lost on the ends. PBS’s The Blinding of Isaac Woodard reminds how society can change with the help of voices loud enough to be heard.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney of the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.