Estimated 4.6M Americans can't vote in midterms because of felony convictions, new report says

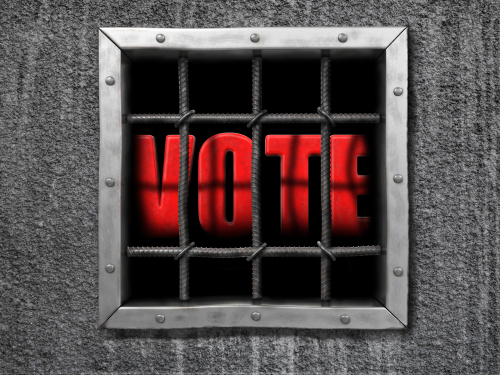

Image from Shutterstock.

The estimated number of people who can’t vote in the United States because of a felony conviction has declined by 24% since 2016, but the total is still large, according to a report released Tuesday by the Sentencing Project.

At estimated 4.6 million Americans won’t be able to vote in the 2022 midterm elections because of current or past felonies, which amounts to one out of 50 adults, according to the report, Locked Out 2022: Estimates of People Denied Voting Rights Due to a Felony Conviction. An overview is here.

Disenfranchisement hits minorities hard. In the Black voting-age population, one out of 19 people are disenfranchised, which is 3.5 times higher than the rate for people who are not Black. In eight states—Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Dakota, Tennessee and Virginia—more than one in 10 Black people can’t vote.

The overall numbers also vary by state, as do the restrictions in each state. In Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee, one out of 13 adults can’t vote because of their criminal history.

The number of people barred from voting has declined partly because of laws or policy changes expanding voting rights. These eight states have expanded voting rights since 2020: California (allowing voting on parole), Connecticut (on parole), Iowa (after completing the sentence, except those convicted of murder), New Jersey (on probation and parole), New York (on parole), North Carolina (on probation and parole), Virginia (after prison) and Washington (after prison).

In addition, Florida voters passed a state constitutional amendment in November 2018 that allowed most people to vote after they completed their sentences. However, a new law signed by the governor the following year required people to pay any court-ordered monetary sanctions to have their voting rights restored.

The disenfranchisement rate also declined because of a decrease in state prison and jail populations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Only two states—Maine and Vermont—have no restrictions on voting by convicted people, even while they are in prison.

The study based its estimates on data that included the number of people who have been released from prison, parole or probation in each state; life expectancy tables; recidivism rates; race data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics; and American Community Survey data.