There is no justice as long as millions lack meaningful access to it

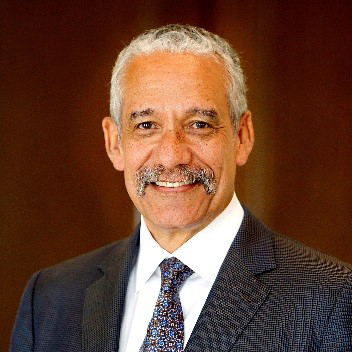

Robert Grey Jr.

Equal access to justice is a pillar of our justice system and a core American value. In fact, it has been fundamental to our self-understanding since even before we were a nation. It informs the principle of righteousness in the Iroquois Confederacy’s Great Law of Peace: “Each individual must have a strong sense of justice, must treat people as equals and must enjoy equal protection under the Great Law.”

It is embodied in one of the chief principles of the Mayflower Compact drawn up in 1620 by the Pilgrims, calling for “just and equal laws.”

It is enshrined in the preamble of the Constitution: “We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish Justice …”

It is engraved on the façade of the U.S. Supreme Court and has been repeatedly cited by the justices who served there, none more eloquently than Justice Lewis Powell: “Equal justice under law is not merely a caption on the façade of the Supreme Court building, it is perhaps the most inspiring ideal of our society. It is one of the ends for which our entire legal system exists…it is fundamental that justice should be the same, in substance and availability, without regard to economic status.”

And it is invoked by Americans of all stripes when they recite the Pledge of Allegiance and proclaim we are a nation “indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

For far too many Americans, however, equal access to justice remains more of a promise than a practice, particularly in the civil justice system where the right to counsel is not guaranteed. Most people who cannot afford to hire a lawyer cannot secure free or even low-cost legal assistance. They are on their own in a system designed by lawyers for lawyers. This has grave consequences for them and for the judges and court administrators charged with maintaining the orderly functioning of our court system.

This significant shortfall between the civil legal needs of low-income Americans and the resources available to address these needs is what is known as the “justice gap.” Last year, the Legal Services Corp., which I am privileged to serve as a member of its board, issued “The Justice Gap: Measuring the Unmet Civil Legal Needs of Low-income Americans.” The report, prepared in conjunction with NORC at the University of Chicago, documents the volume of civil legal needs faced by low-income Americans and assesses the extent to which they seek and receive help. Among its eye-opening findings:

- • Approximately 60 million Americans qualify for LSC-funded civil legal aid because their incomes are at or below 125 percent of the federal poverty guideline—currently $15,075 for an individual and $30,750 for a family of four.

- • Seventy-one percent of low-income households experienced at least one civil legal problem in the past year.

- • One in four low-income households experienced six or more civil legal problems, including 67 percent of households with survivors of domestic violence or sexual assault.

- • Eighty-six percent of the civil legal problems faced by low-income Americans in a given year receive inadequate or no legal help.

- • Low-income Americans seek legal help for only 20 percent of their civil legal problems, and are more likely to seek help for problems that seem more obviously legal, like civil legal problems related to children and custody (48 percent) and wills and estates (39 percent).

Another aspect of the justice gap especially important to the judiciary is the number of unrepresented litigants in the nation’s courts. The National Center for State Courts estimates that in almost 75 percent of civil cases in state courts, one or both parties are unrepresented. The numbers are even higher in some types of high-volume, high-stakes cases. In many American courts, for example, more than 90 percent of tenants facing eviction have no lawyer, as are more than 90 percent of parents in child support cases. Kentucky Chief Justice John Minton has described the situation as a “pro se tsunami hitting the nation’s courts.”

Forcing litigants to represent themselves compromises their access to justice and burdens the court system. Cases involving self-represented parties frequently reach the courts as litigation, when—had counsel been involved—they would have been resolved long before that point. And once they are in court, they take up significantly more time, as judges and clerks must explain information commonly understood by lawyers. The resulting delays affect everyone who needs access to the court system.

More importantly, self-represented litigants are often deprived of true justice since many objectively meritorious claims fail for lack of legal expertise, particularly when unrepresented parties are opposed by experienced attorneys. The wave of self-represented litigants thus threatens the core mission of the courts: delivering fair and timely justice. As Nebraska Chief Justice Michael G. Heavican observed while serving as the president of the Conference of Chief Justices: “The large number of unrepresented citizens overwhelming the nation’s courts has negative consequences not only for them but also for the effectiveness and efficiency of courts. … Frontline judges are telling us that the adversarial foundation of our justice system is all too often losing its effectiveness when citizens are deprived of legal counsel.”

The LSC, the ABA, and other stakeholders in the legal community are doing their best to narrow this justice gap by developing innovative technology, encouraging and supporting pro bono participation by the private bar, and undertaking other initiatives. These are useful, but the country’s civil legal aid network remains chronically underfunded from all sources, particularly from the federal government. The current administration, in fact, has the last two years called for defunding LSC completely, but Congress has resisted this call, and last year increased LSC’s funding by $25 million to $410 million. That figure is still well below what is needed and does not even match the $420 million appropriated by Congress in 2010. From 2007 to 2016, funding per eligible person decreased from $7.54 to $5.85, and at its current level, funding for LSC is less than one-ten-thousandth of the federal budget. It is no wonder that the World Justice Project ranks the United States dead last (36th out of 36th) among high-income countries on the question of whether people can access and afford civil justice.

We are not keeping full faith with a founding principle of our country. There is a reason that equal justice is a core American value. It is essential to our democracy. When a majority of people believe they cannot secure a lawyer or have meaningful access to the court system to resolve their disputes fairly and justly, they lose confidence in the rule of law, the foundation of not only our justice system but of our democracy as well. As the legendary jurist Judge Learned Hand observed: “If we are to keep our democracy, there must be one commandment: Thou shalt not ration justice.”

Robert J. Grey Jr., a senior counsel with Hunton Andrews Kurth in Richmond, Virginia, retired from the active practice of law in March 2016. From 1998 to 2002 he served as chair of the ABA’s House of Delegates and was the first African-American to be an officer of the association. He was elected president of the ABA in 2004, the second African-American to hold the position. In 2009, Mr. Grey was appointed by President Barack Obama, and confirmed by the Senate, to serve on the Board of the Legal Services Corp. In 2012, Grey was elected president of the Leadership Council on Legal Diversity.