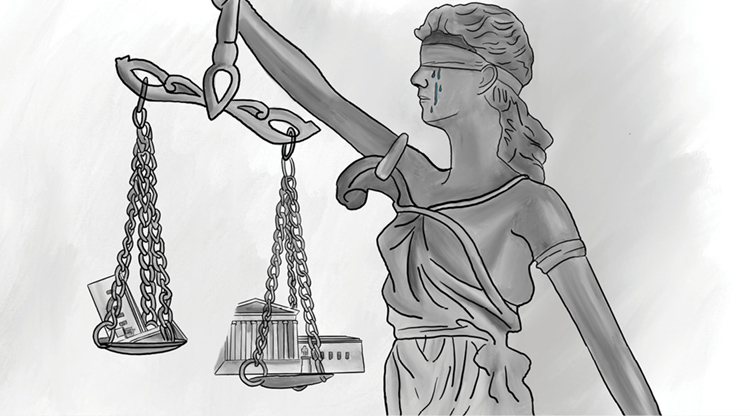

Reigning Supreme: A tipped scale has unbalanced our 'coequal' branches of government

Illustration by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal

In the 232-year history of the United States Supreme Court, 115 justices have been appointed.

Of those 115, two were Black. One was Hispanic.

Five have been women. Zero were Black women.

It’s not a stellar history of diversity, to say the least, and there have been only marginal inroads to change this fact since Thurgood Marshall was appointed in 1967.

Liane Jackson

Liane JacksonKetanji Brown Jackson’s nomination as the first Black woman to serve on the high court is historic and aspirational. But Jackson replaces retiring Justice Stephen G. Breyer, and the court will retain its lopsided 6-3 conservative supermajority as it prepares to hear cases on topics as divisive as affirmative action and gun control. The lack of balance on the court has made finding consensus in the middle challenging, and its rulings are frequently out of step with overwhelming popular opinion.

Judge, jury, executioner

As the nation’s corrosive politics has metastasized, no branch of government has been immune from the dysfunction and partisanship. The Supreme Court is no exception, and that once-venerated institution seems largely to have become a place where democracy goes to die.

I previously wrote about conservatives recognizing early on that the Supreme Court was the brass ring in our “coequal” branches of government that, once controlled, could be weaponized. This prescience has been transformative: In recent years, it’s become clear that an unelected nine-person deliberative body is wielding an outsize amount of power over Congress, the president and the American people.

Court observers worry about an increasing rule by fiat, evidenced by the court’s willingness to overturn cases with decades of precedent and its overuse of the so-called shadow docket—traditionally intended for emergency actions but now routinely used for substantive decisions in a process without oral argument or transparency.

In one brutal example, the court issued a late-evening decision, without opinion, overruling a trial judge and an 11th Circuit panel that had agreed in late January to temporarily stay the execution of an intellectually disabled Alabama death row inmate. Arrogating authority from the lower courts’ factual determination, the justices rejected the stay request, which merely sought to change the preferred method of death and would have postponed the execution date by only a few weeks.

Justice Elena Kagan, noting the court’s lack of transparency, put it best in a blistering dissent to the court’s decision not to hear an emergency challenge to Texas’ controversial abortion ban: “The majority’s decision is emblematic of too much of this court’s shadow-docket decision-making—which every day becomes more unreasoned, inconsistent and impossible to defend.”

Behind the eight ball

Playing the long game through nomination-blocking and rushed-vote tactics, Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., was able to push through hundreds of far-right-aligned judges and three Supreme Court justices during Donald Trump’s presidency, molding a federal judiciary in the image of the minority: Democrats have won the popular vote in seven of the past eight presidential elections.

Now in a frantic, countervailing effort, the Biden administration is focused on filling district and appellate court vacancies as quickly as possible. In his first year in office, Biden filled 11 appellate court openings, almost as many as Trump in his first year, and 29 district court spots, the most of any president since Ronald Reagan. It’s a class that also happens to be the most diverse in history—professionally, racially, by gender and sexual orientation—reflecting the American tapestry.

In comparison, 76% of Trump’s judicial appointees were men, and 84% were white, many of them from prosecutor and corporate ranks. None of Trump’s 54 appeals court nominations was Black, and only one was Hispanic, marking a first since President Richard Nixon.

While Biden faces a challenge confirming judges in states with Republican senators, his record so far is one of the premier achievements of his administration.

Broken republic

Less impressive is the administration’s lack of will to reform the Supreme Court, a top agenda item for Democrats who say the institution must be restructured.

During the first public hearing for Biden’s Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States, Harvard Law School Professor Nikolas Bowie described the court’s power to strike down laws enacted by Congress as an “anti-democratic superweapon” and in written testimony added that historically, “The court has wielded an anti-democratic influence on American law, one that has undermined federal attempts to eliminate hierarchies of race, wealth and status.”

An example of this can be seen in 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder, in which Chief Justice Roberts led the court’s evisceration of the Voting Rights Act. And in subsequent rulings, the conservative, activist wing has demonstrated its hostility toward ensuring the right to vote, rolling out the red carpet for states intent on voter suppression.

In December, the commission issued its final report, examining the SCOTUS problem while carefully avoiding recommendations. The report laid out the pros and cons of proposals, including expanding the court; term limits; rotating justices between the Supreme Court and lower courts; and 18-year staggered terms, which would make appointments to the bench more predictable and equitable.

But despite the extensive review of the issue, it was understood the report was not intended to effectuate reform, as the political power to invoke change is currently nonexistent. As one commissioner told the Wall Street Journal: “We hope that the report’s explications of the issues might be useful a century from now.”

But in centuries past, the framers did not intend for an appointed judiciary, primarily charged with the power to resolve controversy under the law, to become partisan, powerful and entrenched.

In fact, the Supreme Court was once a constitutional afterthought until the beginning of the 19th century, when Justice John Marshall raised the court’s prestige to that of a coequal branch of government and staked constitutional oversight.

In one of his most famous cases, Marbury v. Madison, Marshall established the power of judicial review—the authority of the judicial branch to check the legislative power of Congress and the executive branch.

But judicial review has turned into a slippery slope from neutral checks and balances to abuse of power, with the court blocking the agendas of duly elected representatives and dramatically constraining the federal administrative state.

With approval ratings for the court at an all-time low, justices are in overdrive reinforcing the narrative of its legitimacy. At an April 2021 lecture, Breyer lamented the perception that “politics, not legal merits, drives Supreme Court decisions,” arguing that “if the public sees judges as politicians in robes, its confidence in the courts—and in the rule of law itself—can only diminish, diminishing the court’s power, including its power to act as a check on other branches.” But conversely, it’s the court’s unbridled power that itself must be checked. Court reform will recalibrate our rule of law; maybe public trust will follow.

Intersection is a column that explores issues of race, gender and law across America's criminal and social justice landscape.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.