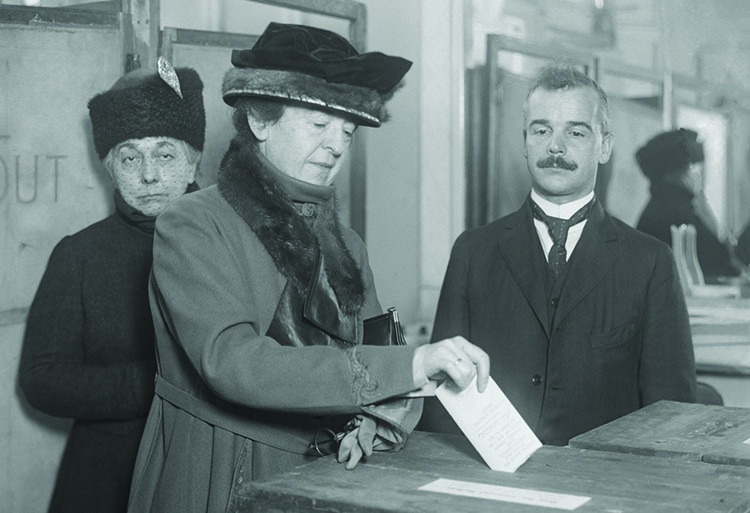

The 19th Amendment and its legacy: Fights remain for voting inclusivity

Image from Shutterstock.com.

During and after the 2020 election, countless news articles were devoted to the voting impact of women: suburban women, Black women, white women, older women, younger women, college-educated women, high school-educated women and just about every other category in which they could be sliced, diced and otherwise grouped.

And indeed, women did have an outsized effect on the election. Black women helped propel Democrat Joseph R. Biden into the presidency, with about 90% backing the former vice president on his way to reaching an historic high of 81.3 million votes. Majorities of Latina voters and suburban white women with college degrees also backed Biden.

On the Republican side, newly recruited female candidates for Congress had huge success, helping the GOP tally a record 35 women for the House and Senate, more than at any other time in the party’s history. This surprised some Democrats who saw notable women in their party lose, including women who lost to men in highly watched Senate contests in Kansas, Texas and Kentucky—proof that Democrats haven’t cornered the market on women’s participation.

At press time, the newly sworn-in 117th Congress had a record number of women in the House and Senate: 144 women, or 26.9% of all members, with a few contests and seats still undetermined, according to Rutgers University’s Center for American Women and Politics.

“Women often carry the election,” says Celina Stewart, chief counsel and senior director of advocacy and litigation for the nonpartisan League of Women Voters.

The 2020 display of female political power came in the centennial year of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, passed by Congress in 1919 and ratified by two-thirds of the states in 1920, which granted women the right to vote.

It was a fitting coda to a 100-year-old story about women achieving access to the ballot box.

But some voting rights activists say the neatly wrapped, “we’ve come full circle” narrative papers over some of the ugly tactics and moral compromises involved with getting the 19th Amendment passed and ratified. They say much work remains to repair racial divisions fueled by some of the early suffragists and to fully enfranchise all voters.

.jpg) Christian Nunes.

Christian Nunes.

“There was a huge focus on the voices of white women” in the 19th Amendment battles, says Christian Nunes, president of the National Organization for Women and the second Black women to serve in that role. The organization is marking its own big anniversary—55 years—in 2021. “A lot of times, Black women’s voices were not heard,” Nunes says.

A multicultural version of American women’s history isn’t widely taught.

A generation of girls raised in the 1970s can still sing the “Schoolhouse Rock” 19th Amendment song that aired during Saturday morning cartoons, and textbooks usually mention suffragists Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Seneca Falls Convention for women’s rights in 1848.

What’s less touted is that Anthony, Stanton and some of their white women allies, though initially aligned with Frederick Douglass and other African-American leaders, eventually opted for what Anthony admitted was a strategy of “expediency”: a conscious decision to fight specifically for white women’s enfranchisement at the expense of nonwhite women. They appealed to white Southern men and women to support women’s suffrage as a way to offset the potential political power of Black men, who had been granted citizenship under the 14th Amendment in 1868 and voting rights—at least on paper—with the 15th Amendment in 1870.

Both Anthony and Stanton died before the 19th Amendment passed. But the damage was done. White women were now seen as a bulwark against enfranchised Black men, whose votes would be further diluted by poll taxes, literacy tests and other racial barriers for decades to come. And it would take almost another century before Black Americans’ right to vote was protected by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. (The Voting Rights Act was substantially diluted in 2013, however, by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which had the effect of allowing states to change their voting laws without federal approval.)

Missed opportunities

The tragedy, says historian and feminist Sally Roesch Wagner, editor of the book The Women’s Suffrage Movement, is that the women’s movement of the 1800s and early 1900s missed several opportunities to become stronger through inclusion.

For example, Native American women had provided a template for inclusive democracy in America long before the first European settlers arrived, with women in some Native American nations controlling clan identity for their children, choosing chiefs and deciding matters of war and peace.

In contrast, the colonial-era legal doctrine of “coverture” held that married women became the property of their husbands, Wagner says. Women couldn’t make legal decisions about their own children, and men could rape or beat their wives without legal consequence.

“We were dead in the law,” says Wagner, an adjunct faculty member at Syracuse University who heads the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation in Fayetteville, New York, which celebrates Gage, a 19th century suffragist, abolitionist and Native American rights activist who parted ways with Anthony over whether states should be able to use Jim Crow laws against people of color.

Wagner wonders how history might have turned out differently had the leading white female suffragists kept their initial alliance with African Americans and added immigrants as well. The women could have used their clout to protect these voters from racist laws.

“When I look at that, I think, ‘What if the suffragists had made different decisions?’” Wagner says.

Sally Roesch Wagner.

Sally Roesch Wagner.

Some organizations are trying to remedy those long-ago slights.

The American Bar Association’s Commission on the 19th Amendment, chaired by Judge M. Margaret McKeown of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, organized several events in 2020 to mark the centennial and highlight the need for political participation by all segments of society. Among them: hosting a conversation with Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in February 2020, sponsoring a traveling exhibit, creating online toolkits for classroom use, producing a podcast and videos and even publishing a 19th Amendment-themed cookbook.

The NOW’s 2020 campaign around the 19th Amendment centennial included an asterisk next to the number “100” to wryly note that “some restrictions still apply.”

Voting restrictions, Nunes says, often hit marginalized communities hardest, including people of color, immigrants and disabled people. Many women are essential workers in the coronavirus pandemic, as well as heads of households and caregivers for older relatives, which means they were hit disproportionately by curtailments on absentee and early voting in the last election.

For example, when Harris County, Texas—home to Houston, the fourth-largest city in the country and an area where Hispanic or Black people together make up about 70% of the population—was given one absentee ballot drop-off location under an order from Gov. Greg Abbott, there was no explicit mention of women of color. But Nunes argues it had the effect of suppressing their votes. “You’re creating enough barriers to make people want to quit,” she says.

Today’s voting rights battles and their attorneys

In 2020, the League of Women Voters went to court in more than 60 cases in state and federal courts and the U.S. Supreme Court, including battles over voter access, redistricting, voter ID laws, voter roll purges and more. The organization, which was founded the same year the 19th Amendment was ratified, saw a tenfold increase in pro bono participation in the last year, says Stewart, chief counsel for the league.

“The amount of work was crushing, just because there was so much going on,” she says. The league had to constantly be proactive, watching for ways to protect voting in the middle of a pandemic, as well as anticipate challenges after ballots were cast.

Some private attorneys contacted the league to offer help; others came via the league’s legal partners. Their backgrounds included election law, tech and intellectual property protection, and their leanings ranged from liberal to conservative, making the team “beautifully diverse,” Stewart says. Many firms lent their top talent, and it showed with close to an 80% success rate in court.

The league says its attorneys help ensure trust in the electoral system, a key part of its goal of encouraging all Americans to have the desire, knowledge and confidence to vote.

George Varghese, a partner at Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr in Boston, signed on to help the league. Together with the nonpartisan Fair Elections Center and the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, Varghese worked on the case Democracy North Carolina v. North Carolina State Board of Elections, which centered on signature requirements and voters’ ability to “cure” or fix minor technical errors with their absentee ballots. After a number of twists and turns, a federal judge ordered the state to provide a curing process.

Nationally, absentee ballots were often requested by older voters, people of color and those concerned about their health during the pandemic. According to Pew Research Center data released after the election, about 46% of all voters in 2020 reported using absentee or mail-in voting, including 38% of Black voters, 45% of white voters, 51% of Hispanic voters and 67% of Asian-American voters. Among people 65 and older, 55% voted by mail, according to the Pew data.

Some North Carolina counties allowed curing of absentee ballots that had minor technical errors while others didn’t. “We said there should be a uniform process—it shouldn’t depend on what county you live in,” Varghese says.

Varghese, a former federal prosecutor who’s worked on high-profile cases like that of a Massachusetts pharmaceutical operation that caused a 2012 nationwide outbreak of fungal meningitis as well as the initial investigation into the Boston Marathon bombing, typically works on cases involving national security or health care fraud. He says he volunteered for the voter access assignment with his firm’s support because voting “is the most fundamental right that we have as citizens in this country.”

It was an arduous effort with a “crazy expedited schedule,” but he says it was worth it to help protect the votes of an estimated 31,000 North Carolinians.

History and its lessons going forward

Outside the courtroom, organizations devoted to increasing women’s political participation continue their work and celebrate their 2020 wins.

Sarah Eagle Heart.

Sarah Eagle Heart.

Sarah Eagle Heart, an Oglala Lakota activist and Emmy Award-winning social justice storyteller and producer, as well as a Women’s March board member, points to the Native American vote in Arizona that was credited with helping Biden win that state by a slim margin of about 10,000 votes.

“The Native vote is often the swing vote in many states,” Eagle Heart says. “I think it’s great that we’re finally getting that recognition.”

Native American women are often the organizers in their communities, whether in responding to public health crises, getting out the vote or keeping cultural traditions alive, Eagle Heart says. But some Native American voters have seen their access to the ballot box restricted, such as in the 2018 fight over North Dakota’s controversial voter ID law, which required voters to provide a street address—but which proved difficult on reservations that only use post office boxes.

Eagle Heart says it’s important to teach young Native American activists the history that was lost under European colonialism: of how Native American women hundreds of years ago helped guide political strategy and property rights, exercised control over their bodies and had the ability to divorce a spouse. “These women really did inspire the suffragettes,” Eagle Heart says.

Jennifer Quinn-Barabanov, a partner at Steptoe & Johnson and former co-chair of her firm’s Women’s Forum who recently organized a virtual panel discussion on the legacy of the 19th Amendment, says the sometimes-messy struggle for women’s suffrage demonstrates how the legal system underpins democracy—and why it’s important to remember who gets left behind when laws are made.

“My takeaway was that we have to be just as focused on the practical as the theoretical,” Quinn-Barabanov says.

Wagner agrees. One of her go-to sayings is “if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.” But she says the legal fights over voting rights in 2020 have made younger voters keenly aware of what’s at stake.

The centennial of the 19th Amendment and its hopeful as well as complicated history offer a moment for reflection, Wagner says. “This has been a rich and wonderful occasion to really rethink our history and start us on another path,” she says.

See also:

ABAJournal.com: “ABA releases a cookbook to mark centennial of 19th Amendment’s ratification”

ABA Journal: “Law Day focuses on 19th Amendment centennial, voting rights”

ABA Journal: “Law Day 2020: Your Vote, Your Voice, Our Democracy”