Criminal charges add twist to Trump lawyers' disciplinary cases

After former President Donald Trump’s defeat in the 2020 election, dozens of lawsuits were filed in federal and state courts alleging election fraud, and judges appointed by both Democrats and Republicans threw them out, finding no evidence to back up the claims. Photo by Evan Vucci/The Associated Press.

When Georgia prosecutors accused former President Donald Trump of election interference in August, the outsized influence of lawyers in the alleged conspiracy veered sharply back into focus.

The indictment in Fulton County Superior Court charges 19 defendants with violations of Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations—RICO—Act, and 40 other charges.

Eight defendants named in the sprawling criminal case are lawyers: including Rudolph Giuliani, Jeffrey Clark, Sidney Powell, Jenna Ellis, Kenneth Chesebro, Ray Smith III, Robert Cheeley and John Eastman. Giuliani and Eastman are charged in the indictment with conspiring with the former president to push a slate of pro-Trump electors from several swing states, including Georgia, in the failed bid to reverse his 2020 election defeat. Chesebro is accused of writing several memos to support the plot to have the electors certify that Trump, not Democrat Joe Biden, was the winner.

On Tuesday, Aug. 22, Eastman’s mugshot and fingerprints were taken at the Fulton County jail in Atlanta. Two days later, he was back in the austere surroundings of the disciplinary courtroom in Los Angeles, seated between his attorneys, with just a few people watching from the gallery. When his disciplinary trial began in June, he was just fighting for his professional career. Now facing criminal liability, much more is at stake than just his law license.

The criminal case could overshadow his bar trial. But Michael J. Teter, the managing director of the 65 Project, a bipartisan group formed by members of the legal community to file complaints against Trump lawyers for professional misconduct, says disciplinary action is important so the same conduct “does not become part of the political arsenal in the future.”

“Lawyers take an oath, and they have a responsibility that’s not just to their client but to the larger legal community, to the profession and to democracy. When you have lawyers who are working against the rule of law [it’s important] to bring a comprehensive system of accountability,” Teter says.

65 Project Advisory Board member Renee Knake Jefferson adds that there also is a deterrent effect in disciplinary trials and says they are important for public confidence in the legal profession, which is self-regulated.

“It’s important that there are consequences in that regulatory process when a lawyer engages in this kind of behavior,” says Jefferson, a law professor and legal ethics expert at the University of Houston.

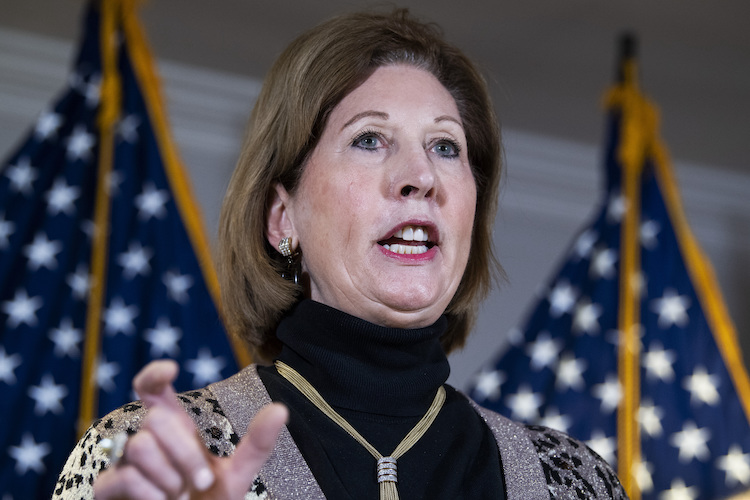

Lawyer Sidney Powell at a news conference at the Republican National Committee on lawsuits regarding the outcome of the 2020 presidential election on Nov. 19, 2020. Photo by Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call via the Associated Press.

Lawyer Sidney Powell at a news conference at the Republican National Committee on lawsuits regarding the outcome of the 2020 presidential election on Nov. 19, 2020. Photo by Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call via the Associated Press.

Lowering the bar

After Trump’s defeat in the 2020 election, dozens of lawsuits were filed in federal and state courts alleging election fraud, and judges appointed by both Democrats and Republicans threw them out, finding no evidence to back up the claims.

What followed was a flurry of complaints to state bar regulators.

In January, the State Bar of California’s Chief Trial Counsel charged Eastman, who advised Trump, spoke at his “Stop the Steal” rally on Jan. 6, 2021, and wrote two memos to support the bogus theory that Vice President Mike Pence had the power to reject certified state electors and reverse Trump’s loss. He faces 11 disciplinary charges under the state’s business and professions code, with the California bar accusing him of acts of “moral turpitude, dishonesty and corruption.”

In June 2021, an appeals court suspended Giuliani’s New York law license. In July, a disciplinary committee in Washington, D.C., recommended the former New York City mayor lose his license to practice law for filing a frivolous election fraud lawsuit in Pennsylvania federal court, and in August a federal judge entered a default judgment against Giuliani for defaming two election workers in Georgia he had accused of election fraud.

Dozens of other lawyers who propped up Trump’s claims are facing ethics complaints. For instance, Clark, a former acting U.S. assistant attorney general, is contesting disciplinary action in D.C. In February, a Texas judge threw out a disciplinary charge against Powell, but in May, the Michigan Attorney Grievance Commission filed a complaint against the lawyer with the state’s attorney discipline board. In March, Colorado’s presiding disciplinary judge Bryon M. Large publicly censured Ellis, another lawyer who was part of Trump’s legal team, for bogus claims she made about the outcome of the 2020 election.

In most states, a disciplinary trial is similar to a bench trial with either a presiding disciplinary judge or volunteer judge, or a panel of two lawyers and a non-lawyer, according to legal ethics expert Wendy J. Muchman, a law professor at the Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law.

Typically, state bar regulators must prove a case with clear and convincing evidence, which is above the standard in civil trials, where a plaintiff has to prove the case by a preponderance of the evidence but below the standard in criminal trials, where the prosecution has the burden of proving the case beyond a reasonable doubt.

After the trial, the hearing panel enters a report and recommendation, and both parties have a right to appeal in most jurisdictions. A panel could decide against discipline, or recommend a period of probation, suspension or disbarment.

“Only the highest court of each state can enter the final order of discipline,” Muchman says.

Free speech?

It didn’t take long for the Georgia RICO indictment to affect Eastman’s disciplinary proceedings. Before his trial resumed in August, his attorney unsuccessfully argued that the disciplinary judge should postpone the trial because Eastman risked revealing evidence that prosecutors could use against him in a criminal trial.

“This changed the picture quite dramatically,” Eastman’s attorney Randall Miller said at a disciplinary hearing, according to the Los Angeles Times (Miller was not available for a Journal interview by press time). “We’re talking about his freedom. We have to operate on all levels with extreme caution here.”

There are echoes of the criminal cases against Trump in lawyers’ defenses. After the federal indictment was filed for election interference against the former president, legal experts debunked Trump’s claim that the First Amendment shields him from criminal liability. Giuliani argued a free speech defense as he faced temporary suspension in New York, but a state appeals court rejected the argument in 2021.

Eastman’s response to the state bar’s complaint argued the First Amendment and California’s free speech protections provide “absolute protection for political speech and legal opinion given in good faith on a matter of public importance.”

But in May, Judge Yvette Roland rejected Eastman’s motion to have Rebecca Roiphe, a professor and the director of the Institute for Professional Ethics at New York Law School, appear as an expert witness in his trial. The judge said she would decide if First Amendment protection is justified and whether Eastman “made false statements and if those statements were made knowingly or with reckless disregard of the truth.”

Eli Wald, a legal ethics professor at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law, says free speech does not give lawyers an “absolute right” to lie on behalf of clients.

“While I see the compelling state interest in the integrity of our adjudication, which is why we don’t allow lawyers to lie on behalf of clients in the courtroom, there is an equally powerful and important state interest in lawyers not lying to the public,” Wald says.

Roiphe declines to comment on the Eastman disciplinary trial. But she says there is a strong case to be made that “lies alone are protected speech” and argues First Amendment protections are stronger for lawyers in disciplinary proceedings.

“The complaints I have seen being pursued against lawyers like Giuliani and others don’t go so far as to suggest that these are lies that were criminal,” Roiphe says. “Disciplinary agencies don’t have the power a prosecutor does to subpoena, convene a grand jury and so forth, so they want a shortcut. And that’s a shortcut that leads you right into First Amendment problems.”

But Wald says the “public outcry” and disciplinary proceedings against Trump lawyers could lead to a “watershed moment.”

“I think that we are at a moment in time where the conduct and involvement of so many lawyers in alleged wrongdoing can serve as a catalyst towards clarifying the role of lawyers as public citizens who cannot lie when the rule of law and the very legitimacy of our democracy is at stake,” Wald says.

Not since the Watergate scandal of the 1970s has the action of lawyers shaken the legal profession to the same degree. Back then, 29 lawyers faced disciplinary proceedings and 18 faced disciplinary action. Lawyers’ role in the scandal led to reforms at the American Bar Association, which a decade later amended its Model Rules of Professional Conduct and mandated ethics classes at law schools.

Model Rule 3.1 bars frivolous claims, and Rule 8.4 prevents lawyers from engaging “in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation.” But the ABA should amend the rules to clarify the role of lawyers outside of the courtroom, Wald says.

Jefferson agrees that the rules should be changed to place constraints on what lawyers can say about the outcome of democratic elections.

“When [lawyers] obtain their law license as part of having the privilege to practice law, they also are accepting constraints on their speech,” Jefferson says. “The First Amendment allows you to lie about whatever you want, and if someone wants to lie about the outcome of an election, they don’t have to be a lawyer—they could give up their law license.”

See also:

“Are defendants in Georgia case against Trump entitled to removal? These standards apply”

“Giuliani ordered to pay over $89K discovery sanction in poll workers’ suit”