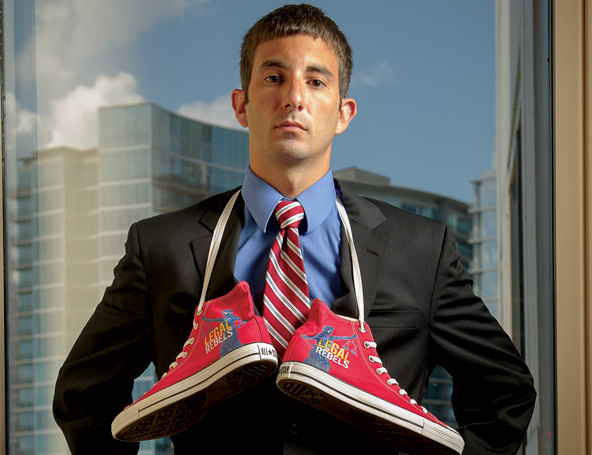

Legal Rebels 2012: If the Shoe Fits...

Photo of model Danniel J. Dixon by Callie Lipkin.

This is our fourth iteration of the ABA Journal’s Legal Rebels, our annual nod to lawyers who are helping change the profession in ways both big and small. These are the innovators—the folks who’ve found a different path, some new way to blend the needs of their clients or their practice, or even their own needs of personal expression, into the way they practice the law. You, our readers, helped us find the 11 we’ve chosen, and they come from anywhere and everywhere: East Coast, West Coast, solo practice, public interest, BigLaw—wherever someone had a good idea that made the legal system a little better, a little faster, a little more accessible to those in need of justice. A transactional lawyer whose practice preaches nonviolence. A purveyor of access to justice. A law student whistleblower. A defender of whistleblowers. A lawyer who specializes in flash mobs. A couple of friends who simply started their own law firm in its own unique mold. These are challenging times for lawyers everywhere, and these are lawyers who are finding opportunity in that challenge. These are our Legal Rebels, the class of 2012. [Look for full profiles and video in our Daily and Weekly newsletters and at LegalRebels.com as they are posted throughout September.]

For a deeper look at our 2012 class of Legal Rebels, head to our website LegalRebels.com for video interviews, an archive of our 70 previous Rebels, the rules for our 2012 Legal Rebels haiku contest and the New Normal—our ongoing discussion about the role of innovation in the fast-changing landscape of the law. And while you’re at it, check out our Law by the Numbers page for a macroeconomic snapshot of the legal industry today.

Photo of Nicole Bradick by Carl Walsh.

NICOLE BRADICK, 32

Portland, Maine

Lawyers with young children may not want full-time work, while many law firms need help but are gun-shy about hiring. Maine lawyer Nicole Bradick found a way to bring these two groups together, with a business she calls Custom Counsel.

Founded in January, it matches lawyers available to do contract work with attorneys who need temporary help. Custom Counsel has 18 lawyers available in Maine and recently opened an office in Washington, D.C.

The mother of two children under age 4, Bradick is also an associate attorney at Portland’s Murray, Plumb & Murray. She began telecommuting two days a week after she had her first child in 2009, and now works there part time. The firm is also a Custom Counsel client.

“Somehow I became known for figuring out the work-life balance thing, and new moms kept approaching me to figure out flexible schedules,” says Bradick. “I noticed a trend for people who just seemed desperate.” Custom Counsel clients need research and writing or stand-ins for court appearances. The lawyers work between 10 and 30 hours a week, and their pay averages $100 an hour. Bradick gets a percentage, which varies according to the agreement made with the contract lawyer. One doesn’t have to be a parent to be a Custom Counsel lawyer, but so far most of its lawyers are. “You can walk away from a position that doesn’t work and do things on your own terms. It’s empowering to know there is an alternative,” Bradick says.

(Click here to read our full profile of Nicole Bradick and watch our video interview with her.)

Photo of Mark Harris by Arnold Adler.

MARK HARRIS, 42

San Francisco

If businesses were to retain Axiom Law’s services, Mark Harris knew his product had to be better—and cheaper—than anything produced by in-house or outside counsel.

He founded the company in 2000 with Stanford MBA Alec Guettel. Initially, Axiom’s lawyers provided ongoing counsel to clients. Outsourcing was added in 2008 and in 2010, Axiom introduced what Harris calls “managed services.” Technology, he says, plays a large role in Axiom’s efficiency, as does changing the way lawyers work. “If you have a big volume of work, the way it’s been done for a long time is dealing with the work that needs to be done, and then break the jobs into tasks, which are assigned values. The values guide decisions on how the work is assigned, based on team members’ experience.

“If you get really good at re-engineering the process, you can also re-engineer the team mix,” he says.

A former junior associate with Davis Polk & Wardwell, Harris left the firm in 1999, lured by the explosion of venture capital during the dot-com boom. “I remember thinking that in a world where everyone was trying so hard to be efficient, why did the law firms get to be so inefficient?”

He recalls that law firm colleagues felt overworked, while clients often thought they were overcharged.

“My observation was that the law firm exchange felt broken, and maybe we could pull that exchange apart and put it back together in a way that made more sense.” Axiom didn’t make a profit until 2003, but it now employs about 1,000 people, 800 of whom are lawyers. For 2011, the company posted revenues of $130 million. That was a 62 percent increase from 2010.

“I’m really excited because I feel—like never before—we are right in the middle of helping transform the way the legal industry operates,” Harris says. “That’s what gets a lot of us excited around here.”

(Click here to read our full profile of Mark Harris and watch our video interview with him.)

Photo of J.M. “Maurits” Barendrectht by Jeff Ruigendijk.

J.M. “MAURITS” BARENDRECHT, 55

The Hague

The Hague is the home of international justice, and Dutch lawyer J.M. “Maurits” Barendrecht would have it be the world’s epicenter of justice innovation.

A law professor and former partner at one of the Netherlands’ largest firms, Barendrecht is now academic director of the Hague Institute for the Internationalization of Law and co-founder of the Innovating Justice Forum. Formed a year ago, the forum nurtures and supports innovative legal initiatives in corners of the planet that have known very little justice, and it does so by whatever means are available—lawyers, courts, nongovernmental organizations, nonlegal organizations, government officials and government administrators.

“We didn’t want The Hague to only be known for classic international law, but also for innovation in the field of justice,” Barendrecht says of the forum, sponsored by the city and the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation. “But we saw that just publishing papers doesn’t have much effect. That triggered our energy and curiosity as to why innovation in the legal sector is so hard. What are the barriers? Who is changing the game and how do they succeed?”

“Try telling lawyers they can improve things by breaking their rules,” Barendrecht says.

In April, the forum hosted a networking conference bringing together members of African and South Asian legal organizations, which usually have very little contact with one another. Many attendees had never thought they were working on the same types of problems, Barendrecht says, but through contacts made at the event, several took fresh looks at new access-to-justice methods and in some cases formed new cross-border partnerships.

“You don’t have to convince people they need a fair, orderly and transparent rule of law,” Barendrecht says. “The main question is how to do it and where to begin.”

(Click here to read our full profile of Maurits Barendrecht and watch our video interview with him.)

“The way I like to think of technology is that it should be almost invisible. It’s nothing more than a tool to help you get your job done.” Photo of Yaacov Silberman by Tony Avelar.

Though the firm and both partners are based in San Francisco, Rimon Law’s ethos emphasizes the flexibility of working anywhere, from the Golden Gate Bridge to the Brooklyn Bridge (above) and beyond. Photo of Michael Moradzadeh by Arnold Adler.

YAACOV SILBERMAN, 32 and MICHAEL MORADZADEH, 32

San Francisco

Michael Moradzadeh and Yaacov Silberman first met in 2005 as associates at Ropes & Gray. At that point many of the trappings of BigLaw—fancy offices, large libraries and individual secretaries—were being scaled back. And perhaps because they hadn’t matured as lawyers during the leather-and-gold-leaf years, they could easily imagine a way of practice without the pomp.

“I liked the high level of work and the people,” Moradzadeh says. “Where I found room for improvement was the unnecessary bureaucracy, politics and inefficiency that led to higher costs and unhappy lawyers.” The two left Ropes & Gray to form Rimon Law in 2008, just a few months before the stock market crashed. Silberman says there had been signs of impending difficulty: Partners were being pressured to bill more hours and clients were taking longer to pay.

“We knew the legal industry was gearing up for a dramatic change and we wanted to stay ahead of it,” Silberman says. “I can’t say we knew just how climactic it was going to be.”

The word rimon means pomegranate in Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic, and in some cultures it has been seen as a symbol for both law and equality. “One reason we did not want our firm name to be our names is because we did not think it should be about us,” Moradzadeh says. “Rimon is much more than me and Yaacov.”

Rimon Law has no billable-hour requirements, and lawyers set their own billing rates with clients. Each lawyer’s percentage is set by contract, so there are no compensation surprises. If a Rimon lawyer needs help with a client, others pitch in at agreed-upon rates paid out of the business originator’s percentage. Silberman says 70 percent of firm revenues are paid to the firm’s lawyers. There are no executive committees and administration is kept to a minimum. The firm’s partners meet twice a month, using videoconference software. They also use Yammer—a business-focused, internal social media site—to communicate. But for Rimon, technology is simply a means to an end.

“The way I like to think of technology is that it should be almost invisible,” Silberman says. “It’s nothing more than a tool to help you get your job done.”

(Click here to read our full profile of Michael Moradzadeh and Yaacov Silberman and watch our video interviews with them.)

“I don’t think of the word ‘criticism’ as a negative word. I think of it as the most helpful thing a person can have.” Photo of Kingsley Martin by Wayne Slezak.

KINGSLEY MARTIN, 53

Chicago

Transactional lawyers compare their work with previous documents to look for similarities and ensure their writing stands up to legal challenges. Kingsley Martin, a former tax lawyer turned techie, developed Kiiac, a software program that can benchmark their work in a fraction of their billable time. Kiiac (knowledge, information, innovation and consulting) is a statistical analysis engine that can analyze and sort information from 100 contracts in a single minute. The software shows lawyers additional and duplicated terms, and determines what common or uncommon text is in the lawyer’s current document.

About 15 clients use Kiiac. Each template costs between $3,000 and $5,000. And Martin, the British-born son of a former Royal Air Force pilot, says he would like to offer something less costly, mostly for small law firms and sole practitioners.

“There’s been little or no incentive for the market-place to do something like this, because they’re paid by the hour. But of course that is changing,” says Martin, who also owns Contract Standards, a free interactive website that shares contract analysis, checklists and clause libraries.

Fans say Kiiac gives attorneys more time to work on negotiating better deals.

“It’s moving lawyers up the value chain, and it’s long overdue,” says Toby Brown, who writes at 3 Geeks and a Law Blog.

When asked whether he prefers exchanging ideas with lawyers or tech-nologists, “everyone” is Martin’s answer. “I don’t think of the word criticism as a negative word,” he says. “I think of it as the most helpful thing a person can have.”

(Click here to read our full profile of Kingsley Martin and watch our video interview with him.)

Photo of Linda Alvarez by Tony Avelar.

LINDA ALVAREZ, 54

Half Moon Bay, Calif.

In contract dealings, attorneys are often the advocates, the fighters, the protectors. For solo practitioner and business consultant Linda Alvarez, that traditional adversarial process simply doesn’t work. After the events of Sept. 11, 2001, Alvarez found herself looking for a way to incorporate nonviolent principles into her practice of law. She found it while dealing with the estate of Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue.

Alvarez had worked for O’Donohue as a business consultant, but after his death in 2008 she discovered that his business relationships lacked many of the most basic formalities.

“I had a choice,” Alvarez says. “I could have sent a typical nasty-gram and shut down those actions, but these were people John loved and who loved John. I had to find a way to powerfully address the harm that was being done to John’s rights and at the same time honor and preserve these essential relationships for John’s family.” Out of that need Alvarez developed a process she calls “discovering agreement.” It helps her clients design agreements that honor the needs and values most important to them, and eschews traditional dispute resolution tactics to create a custom, legally binding system of resolving conflict—one that relies less on the use of legal weapons and more on restoring the original sense of agreement.

Some of her clients say her values-oriented process has revolutionized the way they approach their business. Says Alvarez: “Finding ways to join forces with others and—together—design sustainable, beneficial and enjoyable relationships and enterprises is better than approaching deal-making as an encounter between opposing forces seeking to win an advantage, one over the other.”

(Click here to read our full profile of Linda Alvarez and watch our video interview with her.)

Photo of Vincent Morris by Stephen B. Thornton.

VINCENT MORRIS, 39

Little Rock, Ark.

Vincent Morris loses his job every year. As director of the Arkansas Legal Services Partnership, it’s up to Morris to pitch innovative, effective programs to secure the annual grant money vital to the more than 17,000 legal aid clients—both under the poverty level and just over it—Arkansas’ legal aid organizations serve.

“I joke, but it’s true: I lose my job every year,” laughs Morris. After building houses and working on archaeology digs, Morris decided to pursue a law degree. While attending classes at night—and with little prior experience—he applied for a technology grant to fix legal aid websites.

Morris has received funding for 14 grants during his tenure, which started with an eight-week internship and evolved into a nine-year career at the nonprofit. Every project approved is still going strong and is sustainable for the future. The Arkansas Legal Services Partnership website averages 2 million page views annually, the highest traffic in the state for a legal site. (This in Arkansas, which has a population of 2.9 million.)

As the gulf between those seeking assistance and the services available continues to widen, Morris has concentrated the organization’s efforts on the efficient de-livery of legal help and advice. For instance, the website assembles information and forms client packets for such routine matters as uncontested divorce. The packets include guidance for court testimony; an online wiki is available to answer commonly asked questions. Morris creates most of the content for the website and documents himself, and he is careful to draft everything in plain language. He also created LegalTube, a free video library with a wide range of topics, including consumer protection laws and guides to help Spanish-speaking users navigate the legal aid website. And a live-chat window allows lawyers to answer questions on the spot. “We’re trying to hit the problem from every angle,” Morris says, “so people can use the tools I create to make access to justice an actual meaningful statement.”

(Click here to read our full profile of Vincent Morris and watch our video interview with him.)

“In the past, people with liability would just circle the wagons; they’d never speak up. Now they are breaking their silence in droves.” Photo of Jordan Thomas by Arnold Adler.

JORDAN THOMAS, 42

New York City

Jordan Thomas sometimes meets potential clients in churches, hoping to avoid wiretaps. Others withhold their identity during initial consultations. All are whistleblowers, and many would not have come forward before the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Thomas, a former assistant director with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, helped draft legislative proposals that were incorporated in the Dodd-Frank provisions that established the commission’s new whistleblower program. “I am proud to have helped birth the SEC Whistleblower Program; now I want to raise it,” Thomas says.

Last year, Thomas joined the plaintiffs firm Labaton Sucharow and he now represents whistleblowers full time. Under Dodd-Frank, eligible whistleblowers can get between 10 and 30 percent of their target’s collected sanctions. When a client has a successful case, Thomas receives a percentage of the award. About half of his cases are referred by other lawyers, says Thomas, a 1995 graduate of Los Angeles’ Southwestern Law School and a senior officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve Law Program.

“In the past, people with liability would just circle the wagons; they’d never speak up,” he says. “Now they are breaking their silence in droves.” And because of the SEC Whistleblower Program, he says, individuals with reporting duties can no longer assume it’s safe to remain silent.

Thomas says he has no interest in defending companies facing Dodd-Frank violations, but he does speak with corporate audiences about how they can foster an atmosphere that encourages responsibility and integrity. “Many organizations want to get it right. The question is: How committed are they to getting it right? Lots of organizations focus on the latest compliance trends but fail to establish an ethical culture that deters misconduct.”

(Click here to read our full profile of Jordan Thomas and watch our video interview with him.)

Photo of Kyle McEntee by Michael Schwarz.

KYLE McENTEE, 26

Atlanta

Kyle McEntee may be young, but he certainly doesn’t mind challenging the institutional gatekeepers of the legal profession. As co-founder and executive director of the nonprofit policy organization Law School Transparency, he has been a principal catalyst behind a crusade to overhaul the business of legal education in the United States. Despite the crash of 2008, many law students were still clinging to the notion that a legal education provided a one-way ticket to financial security. But as the economy continued to deteriorate, even law students at elite institutions began wondering whether the rosy employment data they had been given was dependable, or possibly even deceptive.

McEntee and classmate Patrick Lynch took it upon themselves to research those statistics. They incorporated LST to lobby for changes that would benefit students trying to decide whether it was in their best interest to take on massive law school tuition debt, and by 2010 they published a white paper pointing to a problem of transparency in job data reported by law schools. “Transparency is at the base of it all,” McEntee says. “Without transparency, you won’t convince people that the beliefs they have about law school are either wrong or misplaced and can’t be trusted.”

LST’s immensely popular data clearinghouse continues to influence the decisions of prospective law students. The group has also established a dialogue with organizations that can effect change in the profession, like the American Bar Association and the National Association for Law Placement. But LST is at a crossroads. Its grant funding expired in August and McEntee says its future is uncertain.

“My passion lies in policy work,” says McEntee. “To continue the work of LST would take some kind of angel funding,” he adds, “for someone to say: ‘This is worth giving $500,000 to see what LST can do in four to five years.’ ”

(Click here to read our full profile of Kyle McEntee and watch our video interview with him.)

Photo of Ruth Carter by Don McPhee.

RUTH CARTER, 32

Phoenix

Ruth Carter says she was burning out as a mental health therapist when she enrolled at Arizona State’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. At first, she says, she “drank the Kool-Aid” of law school ambition: top 1 percent, BigLaw internship, judicial clerkship. “But I realized very fast that the classic, conservative lawyer ideas weren’t for me.” So she stopped hiding her tattoos, stopped fretting about grades and immersed herself in the areas of the law she truly enjoyed. Oh, and of course there were the flash mobs.

In 2009, then a 1L, Carter participated in Improv Everywhere’s Global No Pants Ride, in which commuters simultaneously doff their trousers, just for the heck of it. Since then, Carter co-founded Improv Arizona and has been building a national reputation as the go-to lawyer for the flash-mob crowd. Carter graduated in May 2011 and opened her Phoenix solo firm in January. She advises clients seeking help with business formation, contract negotiations and information technology. She also blogs on several websites, including as the Undeniable Ruth; there she offers law school survival tips for students and advises readers not to “lose your personality when you get your JD.”

But as flash mob consigliore, the execution of purposeful public silliness remains her passion—and Douglas Sylvester, recently appointed dean of O’Connor law school, has no problem with that. “She is someone who strikes her own path and speaks her own mind, and in this work we don’t have enough people like that.”

(Click here to read our full profile of Ruth Carter and watch our video interview with her.)