As DC Circuit Weighs the Future of Guantanamo Inmates, Some Say Judicial Review Can Harm Military

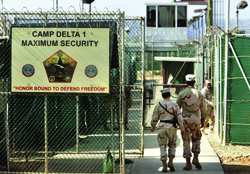

Guantanimo Bay: Of the terrorism suspects detained at the U.S. military prison, 600 have been transferred to other countries and 169 remain, according to an analysis by the New York Times and NPR. AP Photo/Brennan Linsley, File

Federal appeals Judge A. Raymond Randolph is an admirer of the 18th century English critic Samuel Johnson. But it was Nick Carraway, the narrator of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, whom Randolph found himself quoting during a 2010 lecture at the Heritage Foundation.

“They were careless people. … They smashed up things … and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Randolph, senior judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, was not speaking—as was the fictional Carraway—of the rich, “who are different than you and me.” Randolph was addressing the U.S. Supreme Court—specifically, the court’s landmark 2008 case Boumediene v. Bush, which held that detainees at the Guantanamo Bay detention center in Cuba are constitutionally entitled to pursue habeas corpus relief in the federal courts.

What the Supreme Court “smashed up” were statutes depriving federal appeals courts of the jurisdiction to hear such habeas cases, Randolph said. And where the high court dumped the “mess” was in the lap of the D.C. Circuit, leaving the appellate and district courts with the muddle of how to handle piles of petitions from Guantanamo inmates.

Read all the articles in the Patriot Debate series:

WAR POWERS

- • Constitutional Dilemma: The Power to Declare War Is Deeply Rooted in American History by Richard Brust

- • War Powers Belong to the President by John Yoo

- • Only Congress Can Declare War by Louis Fisher

TARGETED KILLINGS

- • Uneasy Targets: How Justifying the Killing of Terrorists Has Become a Major Policy Debate by Richard Brust

- • Targeted Killing Is Lawful If Conducted in Accordance with the Rule of Law by Amos N. Guiora and Monica Hakimi

CYBERWARFARE

- • Cyberattacks: Computer Warfare Looms as Next Big Conflict in International Law by Richard Brust

- • What Is the Role of Lawyers in Cyberwarfare? by Stewart A. Baker and Charles J. Dunlap Jr.

COERCED INTERROGATIONS

- • Probing Questions: Experts Debate the Need to Create Exceptions to Rules on Coerced Confessions by Richard Brust

- • Should We Create Exceptions to Rules Regarding Coerced Interrogation of Terrorism Suspects? by Norman Abrams and Christopher Slobogin

DOMESTIC TERRORISM

- • Insider Threats: Experts Try to Balance the Constitution with Law Enforcement to Find Terrorists by Richard Brust

- • The Threat from Within: What Is the Scope of Homegrown Terrorism? by Gordon Lederman and Kate Martin

THIRD-PARTY DOCTRINE

- • Crashing the Third Party: Experts Weigh How Far the Government Can Go in Reading Your Email by Richard Brust

- • The Data Question: Should the Third-Party Records Doctrine Be Revisited? by Orin Kerr and Greg Nojeim

NATIONAL SECURITY LETTERS

- • Letters of the Law: National Security Letters Help the FBI Stamp Out Terrorism But Some Disapprove by Richard Brust

- • National Security Letters: Building Blocks for Investigations or Intrusive Tools? Michael German and Michelle Richardson, and Valerie Caproni and Steven Siegel

DETENTION POLICY

- • Detention Dilemma: As D.C. Circuit Considers Guantanamo Inmates, Can Judicial Review Harm Military? by Richard Brust

- • Detention Policies: What Role for Judicial Review? by Stephen I. Vladeck and Greg Jacob

“Boumediene ripped up centuries of settled law,” Randolph wrote in a 2011 essay titled “The Guantanamo Mess” for the National Review Online. “The Guantanamo habeas cases march on, hundreds of them, case by case, in our court and in the district court.”

In the article, Randolph—who wrote the appellate decision that the Supreme Court reversed—described the predicament: “Consider one of the most basic issues: Who bears the burden of proof? Must the government show that it is properly holding the detainee? Or is it up to the detainee to show that he is being held improperly? Boumediene contains language that seems to support both positions. … Reading and rereading Boumediene will not give you an answer.”

Nor is Randolph the only D.C. Circuit judge with an opinion on what the Supreme Court can do with Boumediene.

In a blistering concurrence in 2011’s Esmail v. Obama, in which the appeals court denied another detainee’s habeas petition, Senior Judge Laurence H. Silberman doubted the circuit would release any inmate “who is likely to return to terrorism.” And if the executive branch won’t free detainees into the U.S. or another country, then “the whole process leads to virtual advisory opinions.”

“It becomes a charade,” Silberman wrote, “prompted by the Supreme Court’s defiant—if only theoretical—assertion of judicial supremacy, see Boumediene, … sustained by posturing on the part of the Justice Department, and providing litigation exercise for the detainee bar.”

Judge Janice Rogers Brown also chastised Boumediene in her 2011 opinion in Latif v. Obama, in which the appellate court remanded a habeas petition: “As the dissenters warned and as the amount of ink spilled in this single case attests, Boumediene’s airy suppositions have caused great difficulty for the executive and the courts.”

“Luckily,” Brown continued, “this is a shrinking category of cases. The ranks of Guantanamo detainees will not be replenished. Boumediene fundamentally altered the calculus of war, guaranteeing that the benefit of intelligence that might be gained—even from high-value detainees—is outweighed by the systemic cost of defending detention decisions. While the court in Boumediene expressed sensitivity to such concerns, it did not find them ‘dispositive.’ Boumediene’s logic is compelling: Take no prisoners. Point taken.”

STANDING UP FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW

The contentiousness between the D.C. Circuit and the Supreme Court has led many to perceive a “heated debate” after Boumediene over how to handle the future of Guantanamo detainees, according to a 2011 law review article by professor Stephen I. Vladeck of American University’s Washington College of Law. Critics “have accused the D.C. Circuit in general—and some of its judges in particular—of actively subverting Boumediene by adopting holdings and reaching results that have both the intent and the effect of vitiating the Supreme Court’s 2008 decision,” wrote Vladeck in the article, “The D.C. Circuit After Boumediene,” published in the Seton Hall Law Review.

But for others, the Supreme Court’s bequeathing to the D.C. Circuit the duty of sorting the pluses and minuses of detention is a reasonable solution. In fact, Vladeck wrote, Boumediene’s defenders “have stressed both the extent to which Boumediene necessarily left these issues open to judicial resolution and the near-unanimity of the D.C. Circuit in virtually all of the post-Boumediene cases.”

Ultimately, asked Vladeck: “Why should [we] be so afraid of judicial review”? He posed that question in his essay for the book Patriots Debate: Contemporary Issues in National Security Law, published this summer by the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Law and National Security. First, Vladeck wrote, the D.C. Circuit’s jurisprudence has “left the government with far greater detention authority than might otherwise be apparent where non-citizens outside the United States are concerned.”

American University law professor Stephen Vladeck, also senior editor of the Journal of National Security Law and Policy.

Judicial review has also “added a semblance of legitimacy to a regime that had previously and repeatedly been decried as lawless,” Vladeck added, referring to the supervision of Guantanamo.

“The reality is that until judicial review there was no semblance of legal restraint on detention,” Vladeck says in a phone interview. “It’s easy for folks to look at Guantanamo and say that’s a law-free zone. With judicial review the government can now say what we are doing is endorsed not just by Congress but by the courts as well.”

Nor, Vladeck wrote in his essay, has anyone “identified a single example in the Guantanamo litigation in which classified information was improperly disclosed by a detainee’s counsel.”

What’s more, the government has prevailed in every case “in which it appealed a district court’s grant of habeas relief or in which the detainee appealed the denial,” he wrote.

MINDING THE MISSION

But to Gregory Jacob, a partner at O’Melveny & Myers’ D.C. office, the “true cost of judicial review” is how it might harm the U.S. military mission, he wrote in his Patriots Debate response to Vladeck. The ABA committee invited both experts to participate in the discussion.

Considering the nation’s current campaign, and its handling of prisoners of war in the Civil War and World War II, Jacob asked, “how is Professor Vladeck’s expansive judicial review supposed to be administered under such circumstances without seriously compromising our national security interests?”

Absent extraordinary circumstances, wrote Jacob, “the cost to security of judicial interference in active overseas military operations outweighs the liberty cost of potentially erroneous detentions pursuant to those operations.”

Gregory Jacob is a partner at O’Melveny & Myers in D.C.

“My position is that the D.C. Circuit has it about right,” Jacob says in a phone interview, “that there is review but that it has been appropriately deferential to the needs of the military.”

Jacob, who held several positions in the George W. Bush administration, added in his essay: “There are times and places in which the substantial costs in time, energy and resources that necessarily accompany the judiciary’s error-correcting function simply aren’t worth it and to which the framers accordingly never intended to extend constitutional protections.”

In his Patriots Debate essay, Vladeck first chafed at Judge Brown’s implication in the Latif opinion that the balance between gaining detainees’ intelligence and the high cost of defending detention decisions “has precipitated a shift away from detentions and toward targeted killings.” Taking the judge at her word—that the high court hinted at the need for more killings—would be “profoundly unsettling,” Vladeck said.

It would mean that “the true lesson … with regard to military detention is that judicial review is ultimately self-defeating, provoking responses by the political branches that largely eliminate the need for (or availability of) judicial review in the future.”

Vladeck found it ironic “after a decade where not a single U.S. military detainee was freed by order of a federal judge … that ‘take no prisoners’ ” would be Boumediene’s legacy.

Latif merely implies that “the government will have to decide if the potential harm from habeas litigation is sufficiently offset by incapacitating a detainee,” Vladeck says by phone.

Vladeck wrote that he considered it a test of the Supreme Court’s judicial modesty that it rejected several cases to which it might have granted cert, hoping that the other branches would participate.

The court “was willing to draw the line when it needed to be drawn, but each successive decision used only slightly stronger reasoning, leaving room for the political branches to attempt to avoid forcing the court’s hand,” Vladeck wrote in a 2009 article, “The Long War, the Federal Courts and the Necessity/Legality Paradox,” which was published in the University of Richmond Law Review.

Stretching back to the Supreme Court’s earlier war on terrorism decisions in 2004, Vladeck wrote, the high court endeavored to create “a conversation between [it] and the political branches in several acts.”

Vladeck was part of the legal team that successfully challenged the Bush administration’s use of military tribunals in 2006’s Hamdan v. Rumsfeld. He also is a senior editor of the peer-reviewed Journal of National Security Law and Policy.

Ultimately, Vladeck wrote in the 2009 article, “to suggest that courts have no business reviewing conduct carried out under the rubric of military necessity is to give such necessity prominence (if not permanence) over the rule of law.”

AFFECTING THE EFFORT

But to Jacob, the high cost of litigating detainee cases—providing witnesses from the battlefield, quartering detainees during trial, paying attorneys—crimped the American military effort.

For example, he asked in his Patriots Debate essay, “Should we allow [military] operations to be chilled and disrupted by a stream of discovery requests? … Should we rearm [enemy troops] with legal causes of action that will consume significant time and manpower to defend, and further provide them a public platform from which to denounce the United States?”

It is “unsurprising,” Jacob continued, “that the Geneva Conventions … do not even hint at any kind of judicial review for the ordinary detention of military prisoners.”

Before joining O’Melveny & Myers, Jacob served in the White House and in the Justice and Labor departments. He was an attorney adviser in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel and was special assistant to President Bush, with responsibility for formulating policy on immigration, justice, disability, tort reform and other issues. Jacob also advocates for children who are victims of physical or sexual abuse.

In particular, Jacob cited the D.C. Circuit’s 2010 case al-Maqaleh v. Gates, in which the court decided against extending habeas corpus rights to detainees held at the Bagram Air Field in Afghanistan. Jacob called it “probably the most important ‘war on terror’ decision handed down by the D.C. Circuit since Boumediene.”

In a decision written by Judge David B. Sentelle, the court relied on three factors in Boumediene to determine the reach of habeas rights: the citizenship and status of the detainee, and the adequacy of the process through which his status was determined; the nature of the sites where apprehension and detention took place; and the practical obstacles to resolve the detainee’s entitlement.

The court concluded that the writ “does not extend to the Bagram confinement in an active theater of war in a territory under neither the de facto nor de jure sovereignty of the United States.”

In the end, Jacob wrote, the D.C. Circuit backed away from the “nightmare scenario” of disrupting active combat operations for habeas litigation in American-held detention centers around the world.

“From the perspective of the executive branch, the horror is that courts would exert the right and duty that there be habeas review on every battlefield detention,” says Jacob in an interview. “Think about the implications: In World War II there were hundreds of thousands of POWs. Were we supposed to do a habeas review?”

“Maqaleh steps into that breach and says we are not using Boumediene to require us to do that,” he adds. “It’s not a place for us to intervene.”

“In the future the military will simply keep detainees where it captures them,” Jacob wrote in his essay, “preferring the risk of prison breaks and enemy attacks to the certain cost and disruption to intelligence gathering that are inevitably caused by repeatedly being dragged into court.”